脱离热压罐的预浸料:革命性的预浸料技术

By www.carbonfiber.com.cn

在航空航天用复合材料结构件,特别是主结构件制造领域,采用热炉固化、真空袋压预浸料即脱离热压罐的预浸料工艺,以其相对于传统的热压罐预浸料工艺更加灵活、成型更快以及更加经济等优势显示出了极好的应用前景。

图1 这种OOA固化、11.6m长的机翼结构类似于幻影眼示范机的主梁,该机因引领了行业趋势,赢得了《航空周刊》的供应商创新奖这一最高荣誉。两者均由Aurora公司建造。图片来源:Aurora公司

不使用热压罐、只使用真空袋(VBO)大气压力生产航空航天用复合材料,并不是什么新鲜事。用于次级结构件(襟翼、整流罩等)的真空袋压、热炉固化材料系统已行之有效。新的发展是这种材料能够提供不到1%的孔隙率和具备热压罐法产品质量的力学性能,这些特征都是航空航天主结构件,如带集成补强件的机翼、机身和尾翼零部件所要求的。

对OOA工艺的兴趣也促进了树脂传递模塑(RTM)、真空辅助树脂传递模塑(VARTM)和其他液体成型工艺以及最新一代的模压成型热塑性塑料的使用。虽然这些工艺在那些制造高承载结构件的厂商中获得了越来越多认可,但是VBO预浸料,其中涉及传统的手工铺层以及自动化的材料铺放方法,由于形成了独特的优势结合,特别令人感兴趣。

美国空军已确认OOA预浸料对实现快速且具经济成本的制造是至关重要的,这是美国国防部(DOD)打造未来军事平台所需要的,并且空军认为当一个OOA预浸料系统能用于原型设计、生产和备件时,就会带来额外的成本节省。商用飞机原始设备制造商的供应商都将采用OOA材料作为一种途径,来实现生产的灵活性、摆脱尺寸的限制以及模块化/蜂窝工作流程。

然而,许多问题仍然存在。OOA材料的循环时间实际上可能会更长,这是由于低孔隙率所需要的边缘-吸气是一个依赖于时间的过程。其他的问题还包括胶粘剂的相容性、夹层结构的表面质量,以及在铺层中采用自动化。此外,因为这些材料是新的,必须建立一个B-基础设计许用值的完整数据库,这需要时间和金钱。

“抛开炒作的因素,OOA材料是一个很好的工具吗?”波音研究与技术公司非热压罐(预浸料)制造技术项目经理Gail Hahn说道,“是的,但它对行业中所有的应用都适合吗?不一定。”

图2 先进复合材料货运飞机Dornier 328,证明了用$5000万和18个月的时间能够建造一架新的军用运输飞机。该机驾驶员座舱后面被隔开以避免开发新的飞行控制系统的费用,它还使用了一个全复合材料、长达18m的机身。图片来源:洛克希德马丁公司

为什么采用OOA预浸料?

OOA预浸料可以确保均匀的树脂分布,并避免灌注过程中常见的干点和富树脂区。此外,OOA预浸料可以在较低的压力和温度下固化(真空压力相对0.59MPa的典型的热压罐固化压力,在93℃或121℃固化相对传统的177℃热压罐固化)。因此,采用OOA材料生产带集成补强件的大型复合材料结构件,可以在一个周期内固化完成,但所用工具通常是非常复杂和昂贵的,而现在可以实现更加简单并具成本效益的制造。再者,工具和部件的热膨胀系数(CTE)之间的不匹配性在较低的温度下也更小一些,因而更容易掌控产品的质量。此外,OOA预浸料也可以成为防止因固化温差造成部件开裂的一个可能的解决方案。

一个被最广泛引用的OOA材料的好处是其具有降低较高资本和运营成本的潜力。位于俄亥俄州赖特-帕特森空军基地的美国空军研究实验室(AFRL)的防务制造科学与技术项目经理John Russell谈到,美国航空航天局(NASA)分析了为固化直径10m的运载火箭筒身而建造的一个12m×24m热压罐固化的成本,发现它的建造成本约为$4000万,另一项安装加上氮气和电力运行的成本为$6000万。国防部的报告表明,未来的军用飞机项目将要求小批量生产,预算非常少。未来的NASA项目也将在成本上受到更大程度的制约。Russell指出,对于NASA和未来国防部的项目,如远程轰炸机和联合未来战区运输机(后者是C-130的继承者,预期具有55m翼展和43m机身),它们所面临的挑战是如何应对低产量——100架飞机,同时尽可能降低对资金的要求。空军方面预测取消热压罐后,将会带来资金和操作成本上的巨大节省。

商用飞机原始设备制造商的1级供应商对此表示同意,他们看到了OOA预浸料是一种可实现更快速、更敏捷制造的途径。 “我们将进行非热压罐制造,因为在未来这对许多部件而言是可行的。”英国GKN航空航天公司(以下简称GKN公司)技术总监Rich Oldfield解释说,“我们看到它通过一个完全不同的工作流程可为工厂带来效率,相对于大型部件的热压罐工艺,该流程实现了单元式制造,省去了排列等候的时间。” GKN公司也看到这种灵活的制造方式减少了对传统制造的依赖,是实现下一代737和A320单通道喷气客机中复合材料预测含量达到60%~70%的关键。

图3 先进复合材料货运飞机的机身由8个部件组成,它们采用英国先进复合材料集团(ACG)提供的MTM-45预浸料经过OOA固化制成。图片来源:洛克希德马丁公司

20年的革命性开发

据Russell介绍,美国空军研究实验室(AFRL)和国防部高级研究计划局(DARPA)从20世纪90年代中期开始关注预浸料加工,并考虑其如何被用来制作低成本复合材料项目的原型。第一代的OOA VBO材料,包括先进复合材料集团(ACG)的LTM系列,使得大型组合部件的原型能在低温下真空固化,因而制造起来更加便宜。这方面的知名例子包括:Scaled复合材料公司的太空船一号、白骑士一号和全球飞行器,波音公司的X45A无人作战飞机(UCAV),DARPA/洛克希德马丁公司的黑星和麦道公司的猛禽战机。

这些早期的预浸料比较便宜,因为它们在较低温度和真空压力下固化,但它们达不到部件所需的力学性能,而且生产循环时间也较长。

2005~2006年间,两种OOA预浸料系统——ACG的MTM45和氰特工程材料公司(以下简称氰特公司)的CYCOM 5215,已接近热压罐固化预浸料的性能。这两种预浸料具有灵活的固化周期,在66~79℃需要较长的固化时间,但在121℃能提供较短的2h固化。此外,它们在177℃独立固化后,还获得了150℃以上的湿法Tg。

这些系统实现了DARPA所要求的<1%的孔隙率,但其他地方不符合要求。对于其10~12天的粘性期和最高21天的敝模寿命,美国空军研究实验室(AFRL)和NASA都感到不满意,因为大型复杂结构件的铺层和装袋,至少需要3~4个星期。然而,最近ACG和氰特公司已经开发出XMTM-47和CYCOM 5320-1,分别具有21天的粘性期和最低30天的敝模寿命。

2007年,一系列革命性制造技术的开发开始启动,非热压罐(预浸料)制造技术是其中主要的5种技术之一。非热压罐技术由DARPA和波音公司共同资助,并由美国空军研究实验室(AFRL)执行,其既定目标是开发可以提供性能与目前普遍应用的热压罐固化环氧材料相同的OOA系统。ACG公司为该项目提供了MTM45-1、MTM-44和MTM-46材料,氰特公司则提供了CYCOM X5320材料。波音公司评估了3个实验树脂配方,并选定X5320,随后氰特公司把它商业化,成为CYCOM 5320。

一系列的样件被制造出来,并经受了有限的非破坏和解剖评价。HITCO碳复合材料公司建造了一个3.65m×4.57m的增硬表皮主结构样件。Aurora飞行科学公司(以下简称Aurora公司)建成了一个11.6m长的无人驾驶飞行器(UAV)翼梁(在一个单独的开发中,Aurora公司为幻影眼无人机样机建造了一个3部件、跨度为45.7m的OOA固化机翼结构,并因此赢得《航空周刊》的供应商创新金奖)。波音公司为可长途续航的60%尺度的幻影眼无人机样机建造了悬臂和尾翼,按计划该机将在明年初开始飞行试验。波音公司还提交和公开了碳预浸料的材料规范草案和工艺规范草案。

作为该计划第二阶段的一部分,波音下属的圣路易斯公司制造了长达21m的部件,包括一个主梁和3种不同的机翼表皮结构:一种厚板增强的表皮,使用了Grafil公司的HR 40 12K高模量碳纤维;一种增硬的表皮,使用了氰特T40/800B中模量碳单向带以及由氰特Thornel T-650/35 3K碳纤维制成的高强度织物;一种夹层结构的表皮,使用了非金属的蜂窝芯。

这4种部件都使用相同的模具制造,使波音公司能对成品板材按照质量、生产的困难程度、可检测性以及技术成熟水平进行比较。

也许迄今为止,最成功的大型OOA固化结构件的验证来自先进复合材料货运飞机(ACCA)。当空军部长下达任务开发一架新型军用运输机,并且只用$5000万和18个月的时间来完成(国防部下达的指标)时,洛克希德马丁公司用一架Dornier 328飞机参加了美国空军研究实验室(AFRL)的竞争招标。该飞机的驾驶员座舱后面被隔开,以避免开发新的飞行控制系统的费用,并且增加了一个全复合材料、18m长的机身,它分8块制造,整个结构使用了ACG公司的VBO固化MTM-45材料。虽然该项目持续了7个月(已超过最后期限),但是该项目的制造工程师、美国空军研究实验室(AFRL)的Russell表示:“ACCA的花费在预算之内,并且取得了成功。”

图4 组装后的机身内视图。图片来源:洛克希德马丁公司

准备好了,但要等待资格认证

OOA预浸料已达到用于飞机主结构件的热压罐固化系统同等的物理性能,并且几个产品正在进行资格认证当中。先进材料性能国家中心(NCAMP)已完成针对CYCOM 5215和9个MTM45-1产品的许可试验,包括单向和编织石英纤维、平纹编织碳纤维G30-500、高抗拉强度(HTS)12K碳单向带,E-玻纤和6781型S-2玻纤预浸料。纤维由AGY公司提供,织造由JPS玻璃纤维织物公司完成。NCAMP对于与MTM46以及CYCOM 5320-1相似的9个系统的测试也将很快完成。ACG宣布,它将在明年发放其XMTM47系统(“X”很快会被删除)的使用许可,该系统是ACG与NAVAIR合作设立的轻型复合材料结构(LCS)项目的一项研发成果。

然而,在行业内对于资格认证和获得一个完整的许用值数据库也存在着争论。 “我们的OOA技术处于一个准备好的水平,可以相对较快地把它用于产品中。”GKN公司的Rich Oldfield说,“目前只是缺乏材料许可的可用性,因为现在还没有任何针对OOA预浸料系统的B基础许用值数据库。”这一联邦航空局(FAA)认可的统计设计数据,来自复合材料片层和层压板批量试验,是复合材料获得在军用或商用飞机主结构上应用许可的先决条件。ACG公司的研究和技术副总裁Chris Ridgard解释说:“NCAMP不会对机身制造商提供的每项性能进行测试。”它也不会像防卫项目要求的那样测试很多的样品——大约1400~1500件,国防项目则要求3000件。“NCAMP对材料进行测试,并将测试值存储在数据库中,但只有一个特定的防卫平台可以判定一种材料有资格在军机中使用。”美国空军研究实验室(AFRL)的Russell解释道,“通常要花费$300万~500万来开发一个完整的B基础许用值数据库,但还没有一家供应商出面迎接这种挑战。”Russell指出,NCAMP测试提供的数据,不被任何一家公司或防卫平台所独家拥有,比如正在庞巴迪公司和空中客车公司进行的资格认证所提供的数据。

氰特公司的产品经理Mark Ostermeier称,CYCOM 5320和5320-1是在单独的专有项目中进行资格认定的。氰特公司已经宣布它将供应碳纤维复合材料,用于庞巴迪公司Learjet 85飞机的主结构件和次结构件。庞巴迪公司报道该飞机的受压机身将采用氰特公司提供的一种低压、热炉固化及非热压罐的碳纤维。

ACG公司的OOA材料正在空中客车公司进行资格认证。空中客车公司的非热压罐技术项目负责人David Inston解释说:“MTM44-1符合空中客车公司为一个特定的2x2斜纹布所制定的规范。然而,它对一个特定的应用还属于不完全合格。”虽然这是一个机织织物的规格,但它只能用于次级结构而不能用于主结构。该材料的资格认证已接近完成,这标志着MTM44-1将第一次用于实际飞机的部件。空中客车公司与GE航空公司达成一项协议,由后者为A350生产辅助机翼结构,包括机翼检视板和机翼后缘。

Inston指出,空中客车公司虽公布过一个针对MTM44-1单向产品的规范,并已建造了一个主结构的样件,但是还没有对特定应用进行进一步的资格认证测试。“空中客车公司现在正在确定进一步开发OOA材料应用的路线,包括潜在的主结构件用途。”他补充道。

图5 GKN公司使用微波固化,使OOA固化周期缩短了80%(缩至90min)。微波炉比热压罐更具效率,由于它只加热复合材料,因此缩短了加热和冷却的时间,并降低了能耗。图片来源:GKN公司

为了低孔隙度需要较长的时间

然而,制造商警告说,不要对生产中的OOA预浸料产生不合理的期望。例如,它们“快速”制备原型的优势,可能无法转化为“快速”生产,因为孔隙含量目标不能降低。ACG公司的Ridgard解释道:“在OOA工艺中,挥发性物质不仅包括在铺层过程中所包埋的空气,还有环氧树脂暴露在周围空气中时吸收的水分(1%~2%),因此挥发物的去除涉及到一个“边缘呼吸”的策略。为此,层压板的边缘必须与透气材料接触,并且必须采用一种保持空气逃逸路径的方式来布置材料。真空袋材料和工艺过程与采用热压罐工艺是一样的,但真空的质量至关重要,因为夹带空气的抽取是一个随时间变化的过程,而OOA的固化周期通常较长。”氰特公司推荐在OOA预浸料部件初始固化前应保持真空。这是铺层过程中除了压实外所必需的条件,并且在不移除真空袋下进行。保持长度取决于部件的大小和复杂性,范围从4h成型0.6m×0.6m的部件,到16h成型6m×12m、采用共固化增硬的结构。

然而,GKN公司的技术负责人John Cornforth警告说:“当你谈论OOA在真空中要花费更多的时间时,你必须小心,因为一些热压罐材料也需要较长的真空时间。”他指出,对比替代系统是非常困难的,因为真空压力、固化温度和循环时间等特定过程的细节,非常依赖于每个部件的具体情况。

ACG公司的Ridgard声称整体时间的损失真的不会比采用热压罐生产更大。他说:“如果你在176℃固化MTM45-1,例如,你不得不在121℃驻留2h——因为升温过高,使树脂粘度下降过快,从而封闭空气路径,这样你只增加了2h。你也可以灵活选择在121℃或93℃进行较长时间的固化(额外的真空时间是算在内的),然后进行独立的后固化,以获得相同的性能。”

然而,GKN公司可能已发现无需额外循环时间的一种方法。该公司开发了微波固化,可将热压罐和OOA材料的典型固化循环时间缩短达80%——只需90min。据报道,微波只加热复合材料结构,而模具和热炉室保持冷却,从而大大缩短了加热和冷却时间,以及能源消耗。此外,GKN公司还看到了该工艺的另外一个好处,即能够有选择性地固化部件的结构,这可使部分固化的结构整合在一起,将来再共固化成总装配部件。GKN公司利用ACG公司的MTM材料已开始进行技术储备,目前正在用微波固化与传统热压罐材料及工艺进行比较,以确定最佳参数。

夹层表面和OOA胶粘剂

在研究具有重要意义的OOA固化蜂窝芯夹层结构的工作中,ACG公司已经认识到了一些技术上的挑战。Chris Ridgard解释说:“袋压和铺层技术基本上和热压罐固化是相同的,但是芯材的排气变得非常重要。”用于热压罐固化的高压,不允许蜂窝芯内的空气流入层压板的表皮,但是在OOA固化中,这种高压是不存在的。因此,在树脂软化之前,空气必须从夹芯格子中除去,因为较低的OOA压力可能让空气流入表皮中,导致高孔隙率。加拿大McGill大学在2010年SAMPE会议上发表的论文指出,如果在加热前,蜂窝内的压力降低到0.05MPa或更低,空气就不会溢出面板,即空气在固化循环中仍然留在芯材中。Ridgard称,使用一种轻质的玻璃纤维网格布(如54g/m2纱罗织物)作为透气材料,可防止表皮由于芯材内的压力而脱粘。这项技术是在25年前英国航空公司针对复合材料修补所确立的,但一些人认为它不是最佳的解决方案,因为透气材料被层压到夹层中,增加了部件的重量。

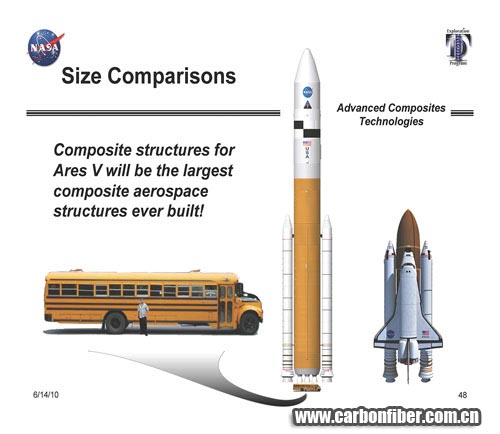

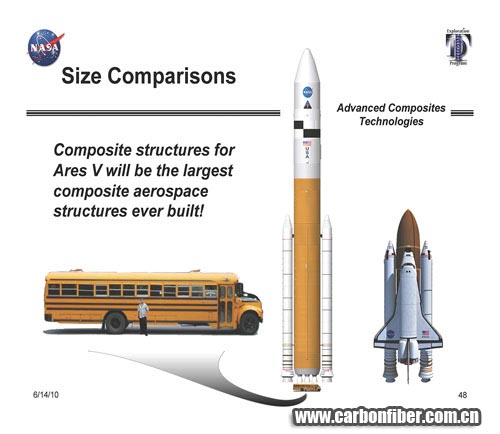

图6 美国国家航空航天局(NASA)的运载火箭(先前的“战神V”)可以成为因采用OOA预浸料而节省大笔金钱的一个很好例证。该项目如果采用12m×24m的热压罐,估计成本达到$1亿。NASA的复合材料与结构高级顾问Mark Shuart相信,一旦直径达10m的火箭筒身部分被证明可以使用OOA工艺,那么航空航天复合材料的制造将发生极大的变化。图片来源:NASA

膜状胶粘剂的发泡,也可以使空气迁移到表皮,这会影响胶粘带的形成,进而损害表皮和芯材的粘接质量。许多用于蜂窝夹芯的普通膜状胶粘剂,在OOA加工中所使用的高真空水平下都会发泡。ACG公司发现,发泡受到膜状胶粘剂载体的类型、蜂格尺寸和固化温度的影响。该公司通过对这些变量进行研究,开发了MTA241,它与MTM材料相容,并且在标准的OOA固化循环内不会发泡。“我们知道,VBO工艺需要一整套的OOA材料。”波音公司的Hahn说道。美国空军研究实验室(AFRL)的Russell也同意这种观点,他说:“膜状胶粘剂和膏状胶粘剂需要与OOA系统相容。当OOA向前发展时,整套材料都必须是相容的。”

OOA蜂窝夹层的另一个问题是避免单次固化时发生表面点蚀。“一个漂亮的OOA夹层表面需要有一层表面齐整的薄膜。”Hahn说道。在最近为2个1.2m×2.4m的测试面板进行的试验中,其中一半使用了表面薄膜,另一半没有使用,结果有薄膜的一半形成了一个更好的表面(没有表面孔隙)。ACG公司不太担忧表面点蚀的问题,因为其在热压罐固化夹层结构中经常使用表面薄膜作为铜网或其他防雷保护(LSP)材料的载体。ACG公司已开发了MTM246表面改善薄膜,用于它的OOA预浸料,而氰特公司推荐其灵活固化的SurfaceMaster SM 905产品,该产品已被用于许多OOA项目中。

更高的浸渍用于自动化

自动化已成为OOA发展的一个关键领域。非热压罐复合材料的纤维铺放是2009~2011年的一个研发项目,由国防部长办公室(OSD)、美国空军研究实验室(AFRL)、国防后勤局(DLA)和海军研究办公室(ONR)制造技术计划联合资助。该项目的主要目标是开发用于OOA材料的自动纤维铺放(AFP)工艺,包括关键工艺参数的确定,如铺放速率,并通过制造全尺寸的航空航天部件来验证该过程。参加者包括波音圣路易斯公司、GKN公司、HITCO碳复合材料公司、洛克希德马丁公司和Spirit空间系统公司。该项目所使用的自动化设备则来自于ElectroImpact公司、Ingersoll机床公司以及MAG工业自动化系统公司。

据Ridgard称,大多数用于手工铺层的OOA预浸料在一定程度上结合了干纤维的工艺路线,它允许在固化过程中抽取空气,但结果不能形成100%的浸渍。这就是使用编织紧密的E玻纤或石英织物的OOA预浸料得不到充分浸渍的原因。然而,在AFP中使用的材料通常要求具有更高的浸渍水平。氰特公司解释说,自动铺带(ATL)中使用的OOA预浸料被分割成152~305mm的宽度,它们不像一般用于AFP的3.2mm、6.4mm或12.7mm窄带子那样敏感。在这些带子中没有干纤维,因为带子铺放时,干纤维移向边缘并聚集,而带子在使用时其边缘会发生脱落。这可以解释为什么用于AFP的OOA预浸料可能和VBO系统虽具有相同的化学性质,但它经常使用最高的浸渍水平。

尽管如此,假定AFP应用的边缘压紧力以及在压力和热量下材料的铺放能力能够减轻空气夹带的问题,氰特公司仍然建议自动铺带采用和手工铺层OOA层压板相同的真空保持度。“这个问题和其他问题正被前面提到的OSD纤维铺放项目所研究探讨,”Russell称,“我们不知道铺带边缘的压力是否将阻断空气路径,这可能会导致孔隙度出现问题。”MTM-45和CYCOM 5320-1将被评估,用于AFP制备的战机机翼表皮部件中。该项目将比较各类自动化设备,并以相同方式跟踪每个样件的铺放时间,所用标准是由联合攻击战斗机(JSF)项目制定的标准。

GKN公司应用其在OOA材料自动化铺层方面超过10年的经验来生产10.5m长、全截面碳纤维复合材料的翼梁样件,该部件和为A400M军用运输机提供的前后翼梁相似,后者是2005~2009年空中客车公司领导的先进低成本飞机结构(ALCAS)项目的一部分。在生产过程中,首先一台西班牙MTorres公司提供的11轴龙门式高速铺带机使用HTS 268g/m2的碳织物MTM44-1预浸料进行铺层;然后这种“扁平带”被自动地转移到碳纤维模具中,模具再被放入一台双隔膜成型压力机中,20min后成型为C型截面半成品;该层压半成品再经过袋压和固化(采用真空压力,所需热量来自集成在模具中的电器元件,初始固化温度为130℃,后固化温度为180℃),一个27mm厚、孔隙率<2%的翼梁部件就得以制造完成。该样件目前正在空中客车英国公司进行测试。

采用加热的模具已经成为GKN公司固化OOA的传统方法。“电或液体加热的模具使你能够不使用热压罐和热炉,”Rich Oldfield说道,“它还允许更精确地控制固化过程,包括局部加热,以适应不同厚度的部件,并消除热点和冷点。”GKN公司认为即使整体加热的模具,其成本也只比标准模具略高一些,但它大大缩短循环时间以及摆脱传统约束的好处提供了一个整体上的经济收益。此外,这项技术也非常有利于更高速的制造。

批评者争辩说,自动化铺层依然依赖大量的资金成本,因此这只是“换汤不换药”。而GKN公司却进行了机器投资,它认为与OOA固化相结合的自动化铺层会带来非常显著的成本节省。自动铺层也不必像典型的手工铺层那样,因使用了预浸料支撑薄膜而需要对产品进行100%的检测。

BMI和超越

OOA双马来酰亚胺(BMI)系统的开发,是OOA工艺发展中一个“安静的革命”。直到Russell在盐湖城召开的秋季SAMPE会议上称:这应该成为每一家公司的一个目标,BMI 才为业界所关注。ACG公司在今年5月份通过演示宣布,它正在开发一种OOA BMI,并将在2011年年底之前完成筛选,2012年产生数据。氰特公司也表示,它将开发OOA BMI。

Maverick公司已生产聚酰亚胺树脂达17年之久,并向预浸料制造商销售这类树脂,如Renegade材料公司。事实上,Maverick公司和Renegade材料公司自2008年以来,就保持密切合作。最近,Akron聚合物系统公司和NASA Glenn公司作为合作伙伴也加入进去,共同开展OOA材料用于高温复合材料应用项目的研究。这项工作受益于最近从美国俄亥俄州获得的Third Frontier Grant基金。该团队自筹和俄亥俄州的配套资金将在两年内达$200万,在此期间,他们将开发使用温度达204~371℃的BMI和聚酰亚胺系统。

Maverick公司总裁兼产品开发总监Robert Gray博士称,聚酰亚胺的使用温度为204~371℃,成本在$220~551/kg之间,而BMI树脂可提供高达177℃的热/湿性能,成本仅为$154~220/kg。BMI树脂更容易加工,因为其不像聚酰亚胺在固化过程中会产生反应副产物,例如水和乙醇。Gray相信大多数加工厂受限于加工只针对高温应用的BMI材料。因此,Maverick公司计划在配制VBO固化预浸料时采用分子量更高的系统以代替粘度非常低的树脂,来减少加工聚酰亚胺的复杂性。

聚酰亚胺复合材料的军事用途包括:喷气发动机中的导向压缩机的定子叶片、发动机背后的排气瓣及外部旁路管道。聚酰亚胺结构也可以应对商业飞机发动机里面和周围的极端环境。Maverick公司和Renegade公司已经确定了聚酰亚胺的许多结构性应用,包括无人机(UAV)和隐形应用。通过提供加工更经济的OOA聚酰亚胺,Maverick公司的项目可以帮助飞机设计师通过减少绝缘和屏蔽的需要来减轻部件的重量。这对于对重量异常敏感的运载火箭和其他空间平台尤为重要。

目前,PMR-15(氰特公司提供的牌号为2237 CYCOM)是行业标准的聚酰亚胺,需要在1.38MPa进行热压罐固化。Gray解释说:“复合材料制造商很少有大型的高温热压罐。如果我们能脱离热压罐加工聚酰亚胺,就可以极大地增强高温复合材料部件供应商的能力,并扩展这些轻质材料的应用。”

然而,推动OOA BMI的因素是什么呢?行业顾问Jeff Hendrix认为,大多数要求耐热温度在135℃以上的BMI和聚酰亚胺部件都被用于发动机中,并且通常要求它们的尺寸不是很大。这些部件适合于目前的热压罐工艺,实际上大多数是模压成型的。“不是使用温度高促使人们选择BMI,而是其在较低温度下的卓越缺口冲击性能使它们对许多方案都有吸引力。”Hendrix解释道,“真正令人满意的OOA系统是其可以在82~121℃范围内匹配BMI的缺口冲击性能,这对环氧树脂基系统颇为理想。”

美国空军研究实验室(AFRL)的Russell表示同意,并指出:“5250-4 BMI(氰特公司生产)被大量地用于JSF项目中,该应用不需要较高的工作温度,选择5250-4 BMI仅仅是因为其热/湿性能提供了更高的比刚度和比强度,进而能够实现更轻的结构。”

Russell还看到了将来的项目对于更高耐温性能的需求,他说:“一些涉及联合未来战区运输机的概念,将催生一种类似于巨大的F-22的运输机,其发动机紧挨着机身,排放的废气穿过水平尾翼表面。这些主结构的温度可能会超过环氧树脂的耐热能力。因此,我们对OOA BMI感兴趣。”Russell称,NASA对BMI产生兴趣的原因是,在运载火箭的头锥使用BMI可以避免使用昂贵、笨重的绝缘材料。单单减轻重量就足以证明使用更贵的BMI是合理的,更不用说它还有利于原材料和劳动力的节省。“我们与Stratton复合材料公司有$60万的合作项目涉及非热压罐BMI的开发。”Russell指出。

波音公司的Hahn说:“有些人看不到OOA BMI所带来的许多好处。作为一家飞机制造商,我会问材料供应商,他们是否有一种OOA BMI可在相当低的固化温度下可以达到足够的初始强度。因为开发新的项目时,所要求的使用温度通常升高而不是下降。”

不再使用热压罐吗?

NASA的复合材料结构高级顾问Mark Shuart谈到,当截面直径为10m的部件被证明可以采用OOA成功加工时,航空航天复合材料的制造将会呈现很大的相同。但有些人会说没有那么简单。“对于要采用的技术来说,它必须具有经济意义。”Hahn说道。Hendrix表示同意。“如果你的生产计划已经有了一个热压罐和材料数据库,那么你不必刻意采用OOA,”他说道,“只有从原型到生产更经济,或者为大型共固化结构件减少模具的复杂性,才会有意义。”

氰特公司的Mark Ostermeier预测,OOA中会更加占据主导地位。但他警告说,航空航天业将仍然是保守的。“庞巴迪公司的Learjet机型在谋求一个全OOA复合材料机身方面已经迈开了一大步,”他说道,“但大多数厂家的大型商业结构件可能还在等等再看。”

Ostermeier看到军用航天航空领域走向OOA的速度比商用飞机更快,并且如果NASA可靠地生产出非热压罐的运载火箭,他预测这可以相当大地改变复合材料的制造方式。Hendrix对此保持怀疑,他说:“我相信OOA的前途是光明的,但人们应该小心,因为他们认为它十分便宜。”

Hahn认为,OOA用于实际生产和研发项目的功效比较是一个大问题,决策的推动力往往是一个项目的截止日期。“我们正在考虑的OOA材料的成本与使用的热压罐主结构材料相同,”她说道,“如果这些OOA材料允许我们在6周内完成模具,然后更快速地进行原型开发和生产,那么它们可以在针对某一应用的商业开发中获胜。”

性能要求:CAI与OHC

美国空军研究实验室(AFRL)非热压罐研究项目的负责人John Russell最近在犹他州盐湖城召开的秋季SAMPE会议上宣称:“使用没有微裂纹的高模量纤维,可使我们提高25%的缺口冲击性能。”尽管OOA预浸料供应商在减少纤维微裂纹方面做得不是很多,但ACG公司已经宣布其XMTM47材料将于明年商业化,该材料的设计基于120℃的使用温度及所要求的缺口性能的改善。缺口压缩强度通常采用开孔压缩(OHC)实验来测量。ACG的XMTM47材料的目标是104℃湿法OHC 达到43ksi。现有的一个更韧性的系统如MTM45-1的OHC约为35ksi。

然而,根据NCAMP(国家先进材料性能中心)副主任Yeow Ng所言,如果OOA预浸料被用于商用飞机,则其压缩后抗冲击性能(CAI,表明损伤容许度)将增加。在Stephen Trimble为《Flight Daily News》最新撰写的文章中,Ng指出,MTM45-1达不到商业飞机监管机构所要求的强度公差。 波音787结构的冲击后压缩(CAI)强度的测量值是40s(ksi),但MTM45-1的CAI 值在30ksi以下。

ACG公司的研究和技术副总裁Chris Ridgard回应道:“许多用在Hawker Beech、Embraer、Gulfstream以及庞巴迪飞机中的结构件都是用热压罐固化Hexcel 8552(CAI≈30 ksi)和氰特977-2(CAI≈37ksi)预浸料制成的。”他还指出,用于Learjet 85、正在进行资格认证的CYCOM 5320,其公布的CAI值为26.5ksi。他说:“在OOA成为一种趋势之前,这种辩论已经存在很久了,它起始于20世纪70年代的热压罐材料和建立在特定应用需求基础上的不同设计理念。”曾是英国航空航天公司结构工程师的Ridgard解释道:“军事上的应用是被缺口应变推动的。军事应用要求结构上的任何地方都可有一个孔存在,并提供一定程度的余量用于战斗损伤和螺栓的维修。因此,军用飞机都倾向于使用具有较高OHC值而韧性较低的树脂系统。” 他继续说道,“对于具有相对较少扣件的大型结构件的大型商用飞机来说,一些飞机制造商偏好使用具有极高CAI值和高破坏应变的高增韧树脂系统。”

ACG公司称将开发一种CAI高于40s的OOA系统,这是一种高度增韧的系统,用于商用飞机领域。氰特公司称,这也将是其下一个工作的重点。当被问及是OHC还是CAI推动Aurora飞行科学公司的无人机设计时,该公司的结构工程师Ed Wen回应道:“两者都有推动作用。”这与波音公司Gail Hahn的观点一致:“我们知道采用不同材料系统的重要性,因此我们将采用一系列的OOA预浸料来满足不同的设计要求。”

真空粘接蜂窝夹层

在《先进复合材料的保养和维修》一书(由汽车工程师协会所属的Warrendale公司在1997年出版)中,英国航空公司拥有复合材料制造和修复24年经验的Keith Armstrong博士讲述了有关“在蜂窝中,单独用0.1MPa的真空获得足够的膜状胶粘剂的粘合压力”的问题,他写道:当真空泵开始从真空袋中抽取空气时,一些空气从蜂格中去除,尤其是靠近板材的边缘。然而,当真空压力增加时,膜状胶粘剂在蜂格的两端形成一个密封,并且空气不再被抽取。

在英国航空公司的试验中,一块边长为0.3m的正方形测试板因真空条件下加热造成的内部压力而不能在中心区域粘接。Armstrong称,在120℃固化过程中,甚至更高的180℃固化中,蜂格内的压力将增加1.5倍,因此他建议相应地减小蜂窝夹层内的压力。对于120℃的固化,如果一个0.1MPa的真空施加于蜂窝夹层,则夹层内的压力在加热之前需要减小到4MPa。Armstrong解释道:“这种非穿孔蜂窝板的制造技术,是在胶粘剂和蜂窝之间夹层的一个面上使用了一种合适的织物。英国航空公司选用了一种无纺聚酯单丝织物,有时也被称为定位布,它通常用作膜状胶粘剂的载体,具有较低的吸水性能。

他强调说,无论选择什么织物,其厚度不应超过0.076mm(英国航空公司选用的两层织物的厚度为0.038mm),膜状胶粘剂应包括1层1.36kg/m3层或2层0.096kg/m3层,以确保能有足够的胶粘剂量来吸附织物,并且在表皮和蜂格末端之间形成充分的胶粘带。

原文资料:

Out-of-autoclave prepregs: Hype or revolution?

Producing aerospace composites without an autoclave, using vacuum-bag-only (VBO) atmospheric pressure, is nothing new. Vacuum-bagged, oven-cured material systems for secondary structures (flaps, fairings and the like) are well established. What is new is the ability for such materials to deliver the less than 1 percent void content and autoclave-quality mechanical properties required for aerospace primary structures, such as wings, fuselages and empennage components with integrated stiffeners.

Interest in OOA processing also has spurred the use of resin transfer molding (RTM), vacuum-assisted RTM (VARTM) and other liquid molding processes as well as the latest generation of compression molded thermoplastics (see “Aerospace-grade compression molding,” under "Editor's Picks," at top right). Although these processes are gaining acceptance among those who fabricate highly loaded structures, VBO prepregs, which encompass traditional hand layup as well as automated material placement methods, are of particular interest due to a combination of unique advantages.

The U.S. Air Force has identified OOA prepregs as vital to achieving the fast and affordable manufacturing that the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) will require for future military platforms, and the Air Force sees additional cost savings when one OOA prepreg system can be used for prototyping, production and spares. Suppliers to commercial aircraft OEMs see OOA materials as a way to achieve manufacturing flexibility, freeing them from size constraints and enabling modular/cellular workflows.

Yet many issues remain. OOA cycle times might actually be longer, due to the time-dependent process of edge-breathing required for low void content. Other issues include compatibility of adhesives, surface quality of sandwich structures, and using automation in lay-up. Also, because these materials are new, a complete database of B-basis design allowables will have to be established, requiring time and money.

“Aside from the hype, is OOA a good tool?” asks Gail Hahn, Non-autoclave (Prepreg) Manufacturing Technology program manager at Boeing Research & Technology (St. Louis, Mo.), “Yes, but is it a game changer for all applications in the industry? Not necessarily.”

Why OOA prepreg?

OOA prepregs ensure even resin distribution, avoiding the dry spots and resin-rich pockets common with infusion processes. Also, OOA prepregs can be cured at lower pressures and temperatures (vacuum pressure vs. a typical autoclave pressure of 85 psi and cure at 200°F/93°C or 250°F/121°C vs. a traditional 350°F/ 177°C autoclave cure). Therefore, tooling for large composite structures with integrated stiffeners that can be cocured in a single cycle, which is typically very complex and expensive, now might be fabricated much more simply and cost-effectively. Further, mismatches between tool and part coefficients of thermal expansion (CTEs) are smaller at lower temperatures and, therefore, more easily managed, positioning OOA prepregs as a potential solution for part cracking caused by cure-temperature differentials.

One of the most widely cited OOA benefits is the potential to reduce high capital and operating costs. John Russell, Defense-Wide Manufacturing Science and Technology program manager for the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio), relates that NASA explored the costs of building a 40-ft by 80-ft (12m by 24m) autoclave to cure 10m/33-ft diameter launch vehicle barrels and found that it would cost roughly $40 million to build and another $60 million to install, plus the cost of nitrogen and power to operate it. DoD advisories indicate that future military aircraft programs will be produced in small volumes with very small budgets. Future NASA programs will be cost-constrained to an even greater degree. Russell points out that for NASA and for coming DoD programs, such as the Long Range Strike and Joint Future Theatre Lift (the latter a C-130 successor with planned 180-ft/55m wingspan and 140-ft/43m fuselage), “the challenge is how to deal with low production volumes —100 aircraft — while reducing capital requirements as much as possible.” The Air Force foresees a huge savings from the elimination of autoclave capital and operating costs.

Tier 1 suppliers to commercial aircraft OEMs agree, seeing OOA prepregs as a way to attain faster, more agile manufacturing. “We will pursue nonautoclave manufacturing for as many parts as is feasible in the future,” comments GKN Aerospace (Redditch, Worcestershire, U.K.) director of technology, Rich Oldfield. “We see it as a way to bring efficiency to the factory, including an entirely different workflow due to cellular manufacturing vs. large parts queued up for an autoclave.” GKN also sees this flexible manufacturing, which is less reliant on traditional manufacturing monuments, as critical to the task of achieving the forecast 60 to 70 percent composites content on the next generation 737 and A320 single-aisle jetliner programs.

A revolution 20 years in the making

According to Russell, AFRL and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) began to look at tooling prepregs and how they might be used to make prototypes in the Affordable Composites program during the mid-1990s. The first generation of OOA VBO materials, including Advanced Composites Group’s (ACG, Tulsa, Okla. and Heanor, Derbyshire, U.K.) LTM series, enabled cheaper, low-temperature vacuum-cure prototypes of large, unitized parts. Notable examples: Scaled Composites’ (Mojave, Calif.) SpaceShipOne, WhiteKnightOne and Global Flyer, Boeing’s X45A unmanned combat aerial vehicle (UCAV), DARPA/Lockheed Martin’s Darkstar, and the McDonnell Douglas Bird of Prey.

These early prepregs were cheaper because they cure at lower temperatures under vacuum pressure, but they had neither the mechanical properties nor the sufficiently short cycle times necessary for production parts.

By 2005-2006, two OOA prepreg systems — ACG’s MTM45 and Cytec Engineered Materials’ (Tempe, Ariz.) CYCOM 5215 — were approaching the properties of autoclave-cured prepregs. Both prepregs feature flexible cure cycles, requiring longer cure times at 150°F to 175°F (66°C to 79°C) but providing shorter two-hour cures at 250°F/121°C. Additionally, they achieve a wet Tg of more than 300°F/150°C after a 350°F/177°C freestanding postcure.

These systems achieved DARPA’s required <1 percent void content, but fell short elsewhere. The 10- to 12-day tack life and maximum 21-day open mold life were deemed insufficient by both AFRL and NASA because layup and bagging of large, complex structures require, at minimum, three to four weeks. Recently, however, ACG and Cytec have developed XMTM-47 and CYCOM 5320-1, respectively, targeted to a longer tack life of 21 days and minimum 30-day open mold life.

In 2007, the Disruptive Manufacturing Technologies Initiative began, with Non-Autoclave (Prepreg) Manufacturing Technology as one of five concentration areas. Cofunded by DARPA and Boeing, and executed with AFRL, the Non-Autoclave initiative’s established goal was to develop OOA systems that could provide the same performance as currently qualified autoclave-cure epoxy materials. ACG responded with MTM45-1, MTM-44 and MTM-46 and Cytec responded with CYCOM X5320. Boeing evaluated three experimental resin formulations, and selected X5320, which was later commercialized by Cytec as CYCOM 5320.

A range of demonstrator parts were built and subjected to limited nondestructive and dissection evaluations. HITCO Carbon Composites (Gardena, Calif.) built a 3.65m by 4.57m (12ft by 15 ft) hat-stiffened skin primary structure demonstrator. Aurora Flight Sciences (Columbus, Miss.) built a 38-ft/11.6m unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) wing spar. (In a separate development, Aurora built a three-part, OOA-cured wing structure with a 150-ft/45.7m span for the Phantom Eye UAV demonstrator, which won top honors in Aviation Week’s Supplier Innovation awards competition, as a potential game-changer in the industry.). Boeing (Irvine, Calif.) built the boom and empennage for a 60 percent-scale demonstrator of the long-endurance Phantom Eye UAV, which is scheduled to begin flight trials in early 2011. Boeing has also submitted draft material specifications for carbon prepreg and a draft process specification, which are available to the public.

As part of the program’s Phase II, Boeing’s St. Louis operation manufactured 68-ft/21m parts, including a spar and three different wing skin configurations:

A plank-stiffened skin, using Grafil (Sacramento, Calif.) HR 40 12K high-modulus carbon fiber;

A hat-stiffened skin. using Cytec T40/800B intermediate modulus carbon unitape as well as high-strength fabric made from Cytec Thornel T-650/35 3K carbon fiber;

A sandwich construction skin, using nonmetallic honeycomb core.

All were made with the same tooling, enabling Boeing to compare the finished panels in terms of quality, degree of production difficulty, inspectability and technology maturity level.

Perhaps the most successful demonstration of large OOA-cured structure to date is the Advanced Composite Cargo Aircraft (ACCA). When tasked by the Secretary of the Air Force to develop a new military transport aircraft with only $50 million and (indicative of DoD’s future intentions) 18 months to completion, Lockheed Martin (Ft. Worth, Texas) responded to an AFRL Broad Agency Announcement (BAA) competitive solicitation with a Dornier 328, cut off behind the cockpit to avoid the expense of developing new flight controls, and added an all-composite, 60-ft/18m long fuselage, built in eight pieces using ACG’s VBO-cured MTM-45 throughout the structure. Although the program ran seven months past its deadline, AFRL’s Russell, the program’s manufacturing engineer, says ACCA stayed on-budget and was a success (see "Advanced Composite Cargo Aircraft ....” under "Editor's Picks").

Ready but awaiting qualification

OOA prepregs have now reached physical property parity with autoclave-cure systems for primary aircraft structure, and several are already in qualification processes. The National Center for Advanced Materials Performance (NCAMP, Wichita, Kan.) has completed allowables testing for CYCOM 5215 and nine MTM45-1 product forms, including uni and woven quartz fiber, plain-weave G30-500 carbon fiber, high tensile strength (HTS) 12K carbon uni, E-glass, and 6781-style S-2 glass prepreg, with fiber supplied by AGY (Aiken, S.C.) and woven by JPS Glass Fabrics (Anderson, S.C.). NCAMP testing of the same nine systems for MTM46 and also for CYCOM 5320-1 will soon be completed. ACG has announced that it will be releasing allowables for its XMTM47 system (“X” soon to be removed) in 2011 via its Lightweight Composite Structures (LCS) program with NAVAIR.

However, there is debate in the industry with regard to qualification and the availability of a complete allowables database. “We are at quite a high readiness level with our OOA technology and could deploy it into products relatively quickly,” says GKN’s Rich Oldfield, “except for the lack of availability of qualified materials, because there is no B-basis allowables database currently for any OOA prepreg system.” This FAA-approved statistical design data from composite lamina and laminate batch testing is a prerequisite to qualification for use in military or commercial aircraft primary structure. ACG’s VP of research and technology, Chris Ridgard, explains, “NCAMP does not run every test that defense airframers list as necessary.” It also does not run as many samples as defense programs require — approximately 1,400 to 1,500 vs. the 3,000 for defense qualification. “NCAMP tests materials and stores the values in a database, but only a specific defense platform can qualify a material for use on that vehicle” explains AFRL’s Russell. “It typically costs $3 million to $5 million to develop a complete B-basis allowables database, and none of the suppliers has stepped up to the plate just yet.” Russell notes that NCAMP testing offers data that is not held as proprietary by any one company or defense platform, such as that developed in the ongoing qualifications at Bombardier and Airbus.

Cytec product manager Mark Ostermeier says CYCOM 5320 and 5320-1 are being qualified in separate, proprietary programs. Cytec has announced it will supply carbon fiber composite materials for both primary and secondary structures on Bombardier’s (Montreal, Quebec, Canada) Learjet 85, and Bombardier reported that the pressurized fuselage will feature “a low-pressure, oven-cured, out-of-autoclave carbon fiber supplied by Cytec.”

ACG’s OOA materials are in qualification at Airbus. David Inston, project leader, out-of-autoclave technologies at Airbus’ Bristol, U.K. location, explains, “MTM44-1 is qualified with an Airbus specification for a particular 2x2 twill fabric. However, it is not fully qualified yet for a specific application.” Although this is a woven fabric specification and, therefore, will be used for secondary rather than primary structure, qualification is nearly complete and marks the first use of MTM44-1 for an actual aircraft part. Airbus has an agreement with GE Aviation (Hamble, U.K.) for the production of secondary wing structures for the A350, including wing access panels and trailing edge details. Inston notes that Airbus does have a specification published for an MTM44-1 unidirectional product, but no further qualification testing has been launched yet for a particular application, although a primary structure demonstrator has been built. “Airbus is in the process now of defining its road map to further develop OOA materials, including potential use in primary structures,” he adds.

Long time for low porosity

Manufacturers, however, warn against unreasonable expectations for OOA prepregs in production. Their reputation for “fast” prototyping, for example, might not translate to “fast” production, where void content goals can’t be compromised. ACG’s Ridgard explains that in OOA processing, removal of volatiles, which include not only air entrapped during layup but also the moisture (1 to 2 percent) that epoxies absorb when they are exposed to ambient air, involves an “edge-breathing” strategy. The laminate edges must be in contact with the breather and materials must be arranged in a way that maintains air escape paths. The vacuum bag materials and sequence are the same as with autoclave processing, but vacuum quality is vital, and because entrapped air extraction is a time-dependent process, OOA cure cycles are typically longer. Cytec recommends a vacuum hold before initiating cure for parts made using its OOA prepregs. This is in addition to any debulks required during layup and is performed without removing the bag prior to cure. Hold length depends on the part size and complexity, ranging from as low as four hours for a 2-ft by 2-ft (0.6m by 0.6m) part to 16 hours for a 20-ft by 40-ft (6m by 12m) structure with cocured hat stiffeners.

But John Cornforth, GKN Aerospace’s head of technology, cautions, “You have to be careful when you talk about OOA taking more time in vacuum, because some autoclave materials also require long vacuum times.” He notes that it is very hard to compare alternative systems because the specific process details of vacuum presssure, cure temperatures and cycle times become very dependent upon the specifics of each part.

ACG’s Ridgard asserts that the overall time penalty is really not any greater than with autoclave production: “If you cure MTM45-1 at 350°F [176°C], for example, you have to dwell at 250°F [121°C] for two hours because ramping too high too quickly drops the resin viscosity to where it will block off air paths. You are only adding two hours, plus you have the flexibility of a longer cure at 250°F [121°C] or 200°F [93°C], where the extra vacuum time is built-in, and then do a freestanding postcure to get the same properties.”

GKN, however, may have found a way around the extra cycle time. The company has developed microwave curing, which reduces typical cure cycles for both autoclave and OOA materials by up to 80 percent, to only 90 minutes. Microwaves reportedly heat only the composite structure, while the tooling and oven chamber remain cool, which drastically cuts heating and cooling time, as well as energy consumption. GKN sees an additional benefit in the ability to selectively cure parts of the structure, which could make integrating partially cured structures and then cocuring the final assembly possible in the future. GKN has begun technology readiness development, using ACG’s MTM materials, and is currently comparing traditional autoclave materials and processes with microwave curing, to define optimum parameters.

Sandwich surface and OOA adhesives

In its significant work with OOA-cured honeycomb-cored sandwich structures, ACG has identified some technical challenges. Chris Ridgard explains, “the bagging and layup techniques are basically the same as in autoclave curing, but venting of the core becomes important.” The high pressures used in autoclave curing, which do not permit air inside a honeycomb core to flow into skin laminates, are not present in OOA curing. Therefore, air must be removed from the core cells before the resin softens, because the lower OOA pressure might otherwise allow air to flow into the skin, resulting in high void content. Research performed at McGill University (Montreal, Quebec, Canada) and presented in a 2010 SAMPE paper shows that if pressure inside the honeycomb is reduced to 500 mbar (7.25 psi) or less prior to heating, the air does not escape into the facesheets. Instead, it remains in the core during the cure cycle. Ridgard says a lightweight glass fiber mesh (such as a 54 g/m2 or 1.6 oz/yd2 leno weave) is used as a breather to prevent skin disbonding due to pressure within the core. This technique was established at British Airways for composite repair more than 25 years ago (see “Old is new ...." sidebar, at the end of this article, or click on it under "Editor's Picks"). However, some believe it is not an optimal solution because the breather is laminated into the sandwich, increasing parasitic weight.

Air also can migrate into the faceskins due to foaming of the film adhesive, which compromises the adhesive fillet formation and resulting faceskin-to-core bond quality. Many common film adhesives for honeycomb sandwich will foam under the high vacuum levels used in OOA processing. ACG found that foaming was affected by film adhesive carrier type, honeycomb cell size and cure temperature. The company worked through these variables to develop MTA241, which is compatible with its MTM materials and will not foam during standard OOA cure cycles. “We see that a whole suite of OOA materials is needed for VBO processing,” says Boeing’s Hahn. AFRL’s Russell agrees, “Both film and paste adhesives compatible with OOA systems are needed. As OOA moves forward, the complete materials suite must all be compatible.”

Another issue for OOA honeycomb sandwich is to avoid surface pitting with single shot cures. “Surfacing film is required for a beautiful OOA sandwich surface,” says Hahn. On two recent 4-ft by 8-ft (1.2m by 2.4m) test panels where half used a surface film and half did not, the half with the film produced a better surface without surface porosity. ACG is not too concerned, because autoclave-cured sandwich structures often use a surfacing film as a carrier for copper mesh or other lightning strike protection (LSP) materials. ACG has developed MTM246 Surface Improvement Film for use with its OOA prepregs, while Cytec recommends its flexible-cure SurfaceMaster SM 905 product, which has been used in many OOA projects.

Higher impregnation for automation

Automation has become a critical area for OOA development. Fiber Placement of Out of Autoclave Composites is a 2009-2011 R&D program jointly funded by the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD), AFRL, Defense Logistics Agency (DLA), and the Office of Naval Research (ONR) Manufacturing Technology (ManTech) program. The Fiber Placement program’s chief goals are to develop the automated fiber placement (AFP) process for OOA materials, including specification of key process parameters, such as lay-down rate, and to demonstrate the process through fabrication of full-scale aerospace components. Participants include Boeing St. Louis, GKN Aerospace, HITCO Carbon Composites, Lockheed Martin, and Spirit Aerosystems (Wichita, Kan.). The program will use automated equipment from ElectroImpact (Mukilteo, Wash.), Ingersoll Machine Tools (Rockford, Ill.) and MAG Industrial Automation Systems (Hebron, Ky.).

According to Ridgard, most OOA prepregs for hand layup incorporate dry fiber paths to some degree, which permit air extraction during cure but result in less than 100 percent impregnation. This is why OOA prepregs that use tightly woven E-glass or quartz fabrics are deliberately under-impregnated. However, materials used in AFP typically have higher degrees of impregnation. Cytec explains that OOA prepreg used in automated tape laying (ATL) is slit into 6-inch to 12-inch (152-mm to 305-mm) widths, which are not as sensitive as the typical 0.125-, 0.25-. or 0.5-inch (3.2-, 6.4- or 12.7-mm) narrow-width tapes used in AFP. There can be no dry fibers in the middle of these tapes because they will hang off the edges as the tape is layed, building up and then stripping off the tape edges during application. This is why OOA prepreg for AFP may have the same chemistry as VBO systems, but it often uses the highest level of impregnation possible.

Even so, it is assumed that the compaction forces of the AFP application head and its ability to lay materials down with pressure and heat will mitigate issues with entrapped air. Cytec still recommends the same vacuum hold as for hand layup OOA laminates. This and other issues are being explored in the aforementioned OSD Fiber Placement program, says Russell. “We are not sure if the pressure applied by the tape-laying head will block the air paths, which could result in porosity issues.” Both MTM-45 and CYCOM 5320-1 will be evaluated in fighter wingskin-sized parts made using AFP. The program will compare various types of automated equipment and will track the lay-down time in the same manner for each demonstrator part, using standards developed by the Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) program.

GKN Aerospace applied more than 10 years of experience with automated layup of OOA materials to produce a 10.5m/34.5-ft long, full cross-section carbon fiber composite wing spar demonstrator, similar to the front and rear wing spars it supplies for the A400M, as part of the 2005-2009 Airbus-led Advanced Low-Cost Aircraft Structures (ALCAS) program. An MTorres (Torres de Elorz, Spain) gantry-mounted 11-axis high-speed tape-layer-applied HTS 268 g/m2 (8 oz/yd2) carbon fabric MTM44-1 prepreg. This “flat pack” was then robotically transferred to a carbon fiber tool, placed in a double-diaphragm forming press, and shaped into a C-section in 20 minutes. The shaped spar laminate was then bagged and cured using only vacuum pressure with heat supplied by electrical elements integrated into the tool, and an initial cure of 130°C/266°F with a 180°C/356°F postcure. The 27-mm/1.1-inch thick spar showed less than 2 percent porosity. It is being tested at

Airbus UK.

Heated tools have been GKN’s conventional approach to OOA curing. “An electrically or fluid-heated tool enables you to avoid both autoclaves and oven,” says Rich Oldfield. “It also allows more accurate control of the curing process, including local heating to accommodate parts with different thicknesses, eliminating hot and cold spots.” Even though an integrally heated tool costs slightly more than a standard tool, GKN believes the benefits of greatly reduced cycle time and freedom from monument constraints deliver an overall economic gain. This technology also is much more conducive to higher-rate manufacturing.

Critics contend that automated layup is again dependent on large capital costs, and is really just swapping out one monument for another. But GKN has already made the machine investment, and sees very significant cost savings in combining automated layup with OOA curing. Automated layup also might serve to reduce the burden of 100 percent inspection typical for hand layup because of the use of prepreg backing film.

BMIs and beyond

The development of OOA bismaleimide (BMI) systems has been a “quiet revolution” in OOA processing development. Or it was until Russell claimed, “This needs to be a goal for everyone,” at the Fall SAMPE conference in Salt Lake City, Utah. ACG announced via presentations in May that it is developing an OOA BMI and stated that it would finalize candidates by the end of 2010 and generate data in 2011. Cytec also says it will develop an OOA BMI.

For 17 years, Maverick Corp. (Blue Ash, Ohio) has produced polyimide resins, which they sell to prepreggers like Renegade Materials Corp. (Dayton, Ohio). Maverick and Renegade, in fact, have worked closely together since 2008 and were recently joined by Akron Polymer Systems (Akron, Ohio) and NASA Glenn (Cleveland, Ohio) as partners in an OOA Materials for High-Temperature Composite Applications project. The effort benefits from a recently awarded Third Frontier Grant from the U.S. state of Ohio. The team’s contribution and Ohio’s matching funds will total $2 million over two years, during which BMI and polyimide systems will be developed for service temperatures of 400°F to 700°F (204°C to 371°C).

Dr. Robert Gray, Maverick president and director of product development, reports that polyimides enable service temperatures between 400°F/204°C and 700°F/371°C and cost $100/lb to $250/lb, while BMI resins provide up to 350°F/177°C hot/wet performance and cost $70/lb to $100/lb. But processing BMI resins is a little easier because, unlike polyimides, they do not form reaction byproducts, such as water and alcohol, during cure. Gray believes that most fabricators are limited to processing only BMI materials for high-temperature applications. However, Gray plans to reduce the complexity of processing polyimides by moving away from very low viscosity resins toward systems of greater molecular weight, formulated for VBO-curing prepregs.

Military applications for polyimide composites include stator vanes leading into the compressor in jet engines, exhaust flaps in back of the engines, and outer bypass ducts. Polyimide structures also can handle extreme environments in and around commercial aircraft engines. Maverick and Renegade have identified many structural applications for polyimides, including UAV and low-observable applications. By offering more affordably processed OOA polyimides, Maverick’s program could help aircraft designers cut weight by reducing the need for insulation and shielding, especially on launch vehicles and other space platforms where weight is super critical.

Currently, PMR-15 (supplied by Cytec as CYCOM 2237), the industry-standard polyimide, requires autoclave cure at 200 psi/13.8 bar. Gray explains, “Very few composites manufacturers have large, high-temperature autoclaves. If we can process polyimides out-of-autoclave, we could dramatically expand the high-temp composite parts supplier base and broaden the use of these lightweight materials.”

But what is the driver for an OOA BMI? According to industry consultant Jeff Hendrix, most BMI and polyimide parts that require performance above ~275˚F/~135˚C are used in engines, and don’t typically need to be large. These parts fit into current autoclaves, and most, in fact, are compression molded. “It’s not the upper use temperature that drives selection of BMIs, but the superior notched properties at even lower temperatures that makes them attractive to many programs,” Hendrix explains, adding, “What’s really desired is an OOA system that can match BMI notched properties in the 180°F to 250°F (82°C to 121°C) range, which would ideally be an epoxy-based system.”

AFRL’s Russell agrees, noting that “5250-4 BMI [produced by Cytec] was used

heavily in the JSF [program], even where no elevated service temperature was

needed, simply because it was able to deliver higher stiffness-to-weight and

strength-to-weight ratios due to its hot/wet performance, which means lighter

structures.”

Russell also sees the need for higher temperature performance in future

programs: “Some concepts for the Joint Future Theater Lift vehicle show an

aircraft resembling a giant F-22, with engines embedded next to the fuselage,

dumping exhaust across the horizontal tail surfaces. Temperatures for these

primary structures likely will exceed epoxy capability. Thus, OOA BMIs are of

interest to us.” Russell says that NASA has an interest because the use of BMI

in the nose-cone of its launch vehicles could eliminate costly, heavy insulation

materials. Eliminating that weight alone could justify BMI’s extra cost, not to

mention the material and labor reductions. “We have a $600,000 program with

Stratton Composites Solutions (Marietta, Ga.) to look at developing an

out-of-autoclave BMI,” notes Russell.

Boeing’s Hahn says some people don’t see much benefit in an OOA BMI but others

do, and she can see both sides. “But as an airframer,” she says, “I would ask

material suppliers if they have an OOA BMI that achieves sufficient green

strength at reasonably low cure temperatures because in-use temperature needs

usually go up not down as new programs develop.”

No more autoclaves?

Mark Shuart, senior advisor for Composites & Structures at NASA Langley

(Hampton, Va.), remarks that when 10m/33-ft diameter sections are demonstrated

successfully using OOA processing, aerospace composites manufacturing will never

be the same. But others say it’s not that simple. “For the technology to be

adopted, it will have to make economical sense,” says Hahn. Hendrix agrees. “If

your production program already has an autoclave and a materials database, you

simply cannot make a business case for looking at OOA,” he argues. “It only

makes sense in the case of going from prototyping to production more

economically or reducing tooling complexity for large cocured structures.”

“OOA will become more predominant,” predicts Cytec’s Mark Ostermeier, but he

warns that the aerospace industry will remain conservative. “Bombardier’s

LearJet has taken a major step by pursuing an all-composite OOA fuselage,” he

observes, “but most manufacturers of large commercial structures will probably

wait and see.”

Ostermeier sees military aerospace moving toward OOA faster than commercial

aircraft, and if NASA does produce out-of-autoclave launch-vehicle sections

reliably, he predicts that it could change composites manufacturing quite a bit.

Hendrix maintains his skepticism, “I believe OOA has a bright future, but people

should be careful because they think it is so much cheaper.”

For Hahn, however, the issue is OOA’s utility in real-world production vs. R&D

programs, where the driver for decision-making often is a program deadline. “The

OOA materials we are looking at right now cost the same as the autoclave primary

structure materials in use,” she notes. “But if they allow us to complete

tooling in six weeks, and then proceed to prototyping and production much more

quickly, it could win in trade studies for an application.”

在航空航天用复合材料结构件,特别是主结构件制造领域,采用热炉固化、真空袋压预浸料即脱离热压罐的预浸料工艺,以其相对于传统的热压罐预浸料工艺更加灵活、成型更快以及更加经济等优势显示出了极好的应用前景。

图1 这种OOA固化、11.6m长的机翼结构类似于幻影眼示范机的主梁,该机因引领了行业趋势,赢得了《航空周刊》的供应商创新奖这一最高荣誉。两者均由Aurora公司建造。图片来源:Aurora公司

不使用热压罐、只使用真空袋(VBO)大气压力生产航空航天用复合材料,并不是什么新鲜事。用于次级结构件(襟翼、整流罩等)的真空袋压、热炉固化材料系统已行之有效。新的发展是这种材料能够提供不到1%的孔隙率和具备热压罐法产品质量的力学性能,这些特征都是航空航天主结构件,如带集成补强件的机翼、机身和尾翼零部件所要求的。

对OOA工艺的兴趣也促进了树脂传递模塑(RTM)、真空辅助树脂传递模塑(VARTM)和其他液体成型工艺以及最新一代的模压成型热塑性塑料的使用。虽然这些工艺在那些制造高承载结构件的厂商中获得了越来越多认可,但是VBO预浸料,其中涉及传统的手工铺层以及自动化的材料铺放方法,由于形成了独特的优势结合,特别令人感兴趣。

美国空军已确认OOA预浸料对实现快速且具经济成本的制造是至关重要的,这是美国国防部(DOD)打造未来军事平台所需要的,并且空军认为当一个OOA预浸料系统能用于原型设计、生产和备件时,就会带来额外的成本节省。商用飞机原始设备制造商的供应商都将采用OOA材料作为一种途径,来实现生产的灵活性、摆脱尺寸的限制以及模块化/蜂窝工作流程。

然而,许多问题仍然存在。OOA材料的循环时间实际上可能会更长,这是由于低孔隙率所需要的边缘-吸气是一个依赖于时间的过程。其他的问题还包括胶粘剂的相容性、夹层结构的表面质量,以及在铺层中采用自动化。此外,因为这些材料是新的,必须建立一个B-基础设计许用值的完整数据库,这需要时间和金钱。

“抛开炒作的因素,OOA材料是一个很好的工具吗?”波音研究与技术公司非热压罐(预浸料)制造技术项目经理Gail Hahn说道,“是的,但它对行业中所有的应用都适合吗?不一定。”

图2 先进复合材料货运飞机Dornier 328,证明了用$5000万和18个月的时间能够建造一架新的军用运输飞机。该机驾驶员座舱后面被隔开以避免开发新的飞行控制系统的费用,它还使用了一个全复合材料、长达18m的机身。图片来源:洛克希德马丁公司

为什么采用OOA预浸料?

OOA预浸料可以确保均匀的树脂分布,并避免灌注过程中常见的干点和富树脂区。此外,OOA预浸料可以在较低的压力和温度下固化(真空压力相对0.59MPa的典型的热压罐固化压力,在93℃或121℃固化相对传统的177℃热压罐固化)。因此,采用OOA材料生产带集成补强件的大型复合材料结构件,可以在一个周期内固化完成,但所用工具通常是非常复杂和昂贵的,而现在可以实现更加简单并具成本效益的制造。再者,工具和部件的热膨胀系数(CTE)之间的不匹配性在较低的温度下也更小一些,因而更容易掌控产品的质量。此外,OOA预浸料也可以成为防止因固化温差造成部件开裂的一个可能的解决方案。

一个被最广泛引用的OOA材料的好处是其具有降低较高资本和运营成本的潜力。位于俄亥俄州赖特-帕特森空军基地的美国空军研究实验室(AFRL)的防务制造科学与技术项目经理John Russell谈到,美国航空航天局(NASA)分析了为固化直径10m的运载火箭筒身而建造的一个12m×24m热压罐固化的成本,发现它的建造成本约为$4000万,另一项安装加上氮气和电力运行的成本为$6000万。国防部的报告表明,未来的军用飞机项目将要求小批量生产,预算非常少。未来的NASA项目也将在成本上受到更大程度的制约。Russell指出,对于NASA和未来国防部的项目,如远程轰炸机和联合未来战区运输机(后者是C-130的继承者,预期具有55m翼展和43m机身),它们所面临的挑战是如何应对低产量——100架飞机,同时尽可能降低对资金的要求。空军方面预测取消热压罐后,将会带来资金和操作成本上的巨大节省。

商用飞机原始设备制造商的1级供应商对此表示同意,他们看到了OOA预浸料是一种可实现更快速、更敏捷制造的途径。 “我们将进行非热压罐制造,因为在未来这对许多部件而言是可行的。”英国GKN航空航天公司(以下简称GKN公司)技术总监Rich Oldfield解释说,“我们看到它通过一个完全不同的工作流程可为工厂带来效率,相对于大型部件的热压罐工艺,该流程实现了单元式制造,省去了排列等候的时间。” GKN公司也看到这种灵活的制造方式减少了对传统制造的依赖,是实现下一代737和A320单通道喷气客机中复合材料预测含量达到60%~70%的关键。

图3 先进复合材料货运飞机的机身由8个部件组成,它们采用英国先进复合材料集团(ACG)提供的MTM-45预浸料经过OOA固化制成。图片来源:洛克希德马丁公司

20年的革命性开发

据Russell介绍,美国空军研究实验室(AFRL)和国防部高级研究计划局(DARPA)从20世纪90年代中期开始关注预浸料加工,并考虑其如何被用来制作低成本复合材料项目的原型。第一代的OOA VBO材料,包括先进复合材料集团(ACG)的LTM系列,使得大型组合部件的原型能在低温下真空固化,因而制造起来更加便宜。这方面的知名例子包括:Scaled复合材料公司的太空船一号、白骑士一号和全球飞行器,波音公司的X45A无人作战飞机(UCAV),DARPA/洛克希德马丁公司的黑星和麦道公司的猛禽战机。

这些早期的预浸料比较便宜,因为它们在较低温度和真空压力下固化,但它们达不到部件所需的力学性能,而且生产循环时间也较长。

2005~2006年间,两种OOA预浸料系统——ACG的MTM45和氰特工程材料公司(以下简称氰特公司)的CYCOM 5215,已接近热压罐固化预浸料的性能。这两种预浸料具有灵活的固化周期,在66~79℃需要较长的固化时间,但在121℃能提供较短的2h固化。此外,它们在177℃独立固化后,还获得了150℃以上的湿法Tg。

这些系统实现了DARPA所要求的<1%的孔隙率,但其他地方不符合要求。对于其10~12天的粘性期和最高21天的敝模寿命,美国空军研究实验室(AFRL)和NASA都感到不满意,因为大型复杂结构件的铺层和装袋,至少需要3~4个星期。然而,最近ACG和氰特公司已经开发出XMTM-47和CYCOM 5320-1,分别具有21天的粘性期和最低30天的敝模寿命。

2007年,一系列革命性制造技术的开发开始启动,非热压罐(预浸料)制造技术是其中主要的5种技术之一。非热压罐技术由DARPA和波音公司共同资助,并由美国空军研究实验室(AFRL)执行,其既定目标是开发可以提供性能与目前普遍应用的热压罐固化环氧材料相同的OOA系统。ACG公司为该项目提供了MTM45-1、MTM-44和MTM-46材料,氰特公司则提供了CYCOM X5320材料。波音公司评估了3个实验树脂配方,并选定X5320,随后氰特公司把它商业化,成为CYCOM 5320。

一系列的样件被制造出来,并经受了有限的非破坏和解剖评价。HITCO碳复合材料公司建造了一个3.65m×4.57m的增硬表皮主结构样件。Aurora飞行科学公司(以下简称Aurora公司)建成了一个11.6m长的无人驾驶飞行器(UAV)翼梁(在一个单独的开发中,Aurora公司为幻影眼无人机样机建造了一个3部件、跨度为45.7m的OOA固化机翼结构,并因此赢得《航空周刊》的供应商创新金奖)。波音公司为可长途续航的60%尺度的幻影眼无人机样机建造了悬臂和尾翼,按计划该机将在明年初开始飞行试验。波音公司还提交和公开了碳预浸料的材料规范草案和工艺规范草案。

作为该计划第二阶段的一部分,波音下属的圣路易斯公司制造了长达21m的部件,包括一个主梁和3种不同的机翼表皮结构:一种厚板增强的表皮,使用了Grafil公司的HR 40 12K高模量碳纤维;一种增硬的表皮,使用了氰特T40/800B中模量碳单向带以及由氰特Thornel T-650/35 3K碳纤维制成的高强度织物;一种夹层结构的表皮,使用了非金属的蜂窝芯。

这4种部件都使用相同的模具制造,使波音公司能对成品板材按照质量、生产的困难程度、可检测性以及技术成熟水平进行比较。

也许迄今为止,最成功的大型OOA固化结构件的验证来自先进复合材料货运飞机(ACCA)。当空军部长下达任务开发一架新型军用运输机,并且只用$5000万和18个月的时间来完成(国防部下达的指标)时,洛克希德马丁公司用一架Dornier 328飞机参加了美国空军研究实验室(AFRL)的竞争招标。该飞机的驾驶员座舱后面被隔开,以避免开发新的飞行控制系统的费用,并且增加了一个全复合材料、18m长的机身,它分8块制造,整个结构使用了ACG公司的VBO固化MTM-45材料。虽然该项目持续了7个月(已超过最后期限),但是该项目的制造工程师、美国空军研究实验室(AFRL)的Russell表示:“ACCA的花费在预算之内,并且取得了成功。”

图4 组装后的机身内视图。图片来源:洛克希德马丁公司

准备好了,但要等待资格认证

OOA预浸料已达到用于飞机主结构件的热压罐固化系统同等的物理性能,并且几个产品正在进行资格认证当中。先进材料性能国家中心(NCAMP)已完成针对CYCOM 5215和9个MTM45-1产品的许可试验,包括单向和编织石英纤维、平纹编织碳纤维G30-500、高抗拉强度(HTS)12K碳单向带,E-玻纤和6781型S-2玻纤预浸料。纤维由AGY公司提供,织造由JPS玻璃纤维织物公司完成。NCAMP对于与MTM46以及CYCOM 5320-1相似的9个系统的测试也将很快完成。ACG宣布,它将在明年发放其XMTM47系统(“X”很快会被删除)的使用许可,该系统是ACG与NAVAIR合作设立的轻型复合材料结构(LCS)项目的一项研发成果。

然而,在行业内对于资格认证和获得一个完整的许用值数据库也存在着争论。 “我们的OOA技术处于一个准备好的水平,可以相对较快地把它用于产品中。”GKN公司的Rich Oldfield说,“目前只是缺乏材料许可的可用性,因为现在还没有任何针对OOA预浸料系统的B基础许用值数据库。”这一联邦航空局(FAA)认可的统计设计数据,来自复合材料片层和层压板批量试验,是复合材料获得在军用或商用飞机主结构上应用许可的先决条件。ACG公司的研究和技术副总裁Chris Ridgard解释说:“NCAMP不会对机身制造商提供的每项性能进行测试。”它也不会像防卫项目要求的那样测试很多的样品——大约1400~1500件,国防项目则要求3000件。“NCAMP对材料进行测试,并将测试值存储在数据库中,但只有一个特定的防卫平台可以判定一种材料有资格在军机中使用。”美国空军研究实验室(AFRL)的Russell解释道,“通常要花费$300万~500万来开发一个完整的B基础许用值数据库,但还没有一家供应商出面迎接这种挑战。”Russell指出,NCAMP测试提供的数据,不被任何一家公司或防卫平台所独家拥有,比如正在庞巴迪公司和空中客车公司进行的资格认证所提供的数据。

氰特公司的产品经理Mark Ostermeier称,CYCOM 5320和5320-1是在单独的专有项目中进行资格认定的。氰特公司已经宣布它将供应碳纤维复合材料,用于庞巴迪公司Learjet 85飞机的主结构件和次结构件。庞巴迪公司报道该飞机的受压机身将采用氰特公司提供的一种低压、热炉固化及非热压罐的碳纤维。

ACG公司的OOA材料正在空中客车公司进行资格认证。空中客车公司的非热压罐技术项目负责人David Inston解释说:“MTM44-1符合空中客车公司为一个特定的2x2斜纹布所制定的规范。然而,它对一个特定的应用还属于不完全合格。”虽然这是一个机织织物的规格,但它只能用于次级结构而不能用于主结构。该材料的资格认证已接近完成,这标志着MTM44-1将第一次用于实际飞机的部件。空中客车公司与GE航空公司达成一项协议,由后者为A350生产辅助机翼结构,包括机翼检视板和机翼后缘。

Inston指出,空中客车公司虽公布过一个针对MTM44-1单向产品的规范,并已建造了一个主结构的样件,但是还没有对特定应用进行进一步的资格认证测试。“空中客车公司现在正在确定进一步开发OOA材料应用的路线,包括潜在的主结构件用途。”他补充道。

图5 GKN公司使用微波固化,使OOA固化周期缩短了80%(缩至90min)。微波炉比热压罐更具效率,由于它只加热复合材料,因此缩短了加热和冷却的时间,并降低了能耗。图片来源:GKN公司

为了低孔隙度需要较长的时间

然而,制造商警告说,不要对生产中的OOA预浸料产生不合理的期望。例如,它们“快速”制备原型的优势,可能无法转化为“快速”生产,因为孔隙含量目标不能降低。ACG公司的Ridgard解释道:“在OOA工艺中,挥发性物质不仅包括在铺层过程中所包埋的空气,还有环氧树脂暴露在周围空气中时吸收的水分(1%~2%),因此挥发物的去除涉及到一个“边缘呼吸”的策略。为此,层压板的边缘必须与透气材料接触,并且必须采用一种保持空气逃逸路径的方式来布置材料。真空袋材料和工艺过程与采用热压罐工艺是一样的,但真空的质量至关重要,因为夹带空气的抽取是一个随时间变化的过程,而OOA的固化周期通常较长。”氰特公司推荐在OOA预浸料部件初始固化前应保持真空。这是铺层过程中除了压实外所必需的条件,并且在不移除真空袋下进行。保持长度取决于部件的大小和复杂性,范围从4h成型0.6m×0.6m的部件,到16h成型6m×12m、采用共固化增硬的结构。

然而,GKN公司的技术负责人John Cornforth警告说:“当你谈论OOA在真空中要花费更多的时间时,你必须小心,因为一些热压罐材料也需要较长的真空时间。”他指出,对比替代系统是非常困难的,因为真空压力、固化温度和循环时间等特定过程的细节,非常依赖于每个部件的具体情况。

ACG公司的Ridgard声称整体时间的损失真的不会比采用热压罐生产更大。他说:“如果你在176℃固化MTM45-1,例如,你不得不在121℃驻留2h——因为升温过高,使树脂粘度下降过快,从而封闭空气路径,这样你只增加了2h。你也可以灵活选择在121℃或93℃进行较长时间的固化(额外的真空时间是算在内的),然后进行独立的后固化,以获得相同的性能。”

然而,GKN公司可能已发现无需额外循环时间的一种方法。该公司开发了微波固化,可将热压罐和OOA材料的典型固化循环时间缩短达80%——只需90min。据报道,微波只加热复合材料结构,而模具和热炉室保持冷却,从而大大缩短了加热和冷却时间,以及能源消耗。此外,GKN公司还看到了该工艺的另外一个好处,即能够有选择性地固化部件的结构,这可使部分固化的结构整合在一起,将来再共固化成总装配部件。GKN公司利用ACG公司的MTM材料已开始进行技术储备,目前正在用微波固化与传统热压罐材料及工艺进行比较,以确定最佳参数。

夹层表面和OOA胶粘剂

在研究具有重要意义的OOA固化蜂窝芯夹层结构的工作中,ACG公司已经认识到了一些技术上的挑战。Chris Ridgard解释说:“袋压和铺层技术基本上和热压罐固化是相同的,但是芯材的排气变得非常重要。”用于热压罐固化的高压,不允许蜂窝芯内的空气流入层压板的表皮,但是在OOA固化中,这种高压是不存在的。因此,在树脂软化之前,空气必须从夹芯格子中除去,因为较低的OOA压力可能让空气流入表皮中,导致高孔隙率。加拿大McGill大学在2010年SAMPE会议上发表的论文指出,如果在加热前,蜂窝内的压力降低到0.05MPa或更低,空气就不会溢出面板,即空气在固化循环中仍然留在芯材中。Ridgard称,使用一种轻质的玻璃纤维网格布(如54g/m2纱罗织物)作为透气材料,可防止表皮由于芯材内的压力而脱粘。这项技术是在25年前英国航空公司针对复合材料修补所确立的,但一些人认为它不是最佳的解决方案,因为透气材料被层压到夹层中,增加了部件的重量。

图6 美国国家航空航天局(NASA)的运载火箭(先前的“战神V”)可以成为因采用OOA预浸料而节省大笔金钱的一个很好例证。该项目如果采用12m×24m的热压罐,估计成本达到$1亿。NASA的复合材料与结构高级顾问Mark Shuart相信,一旦直径达10m的火箭筒身部分被证明可以使用OOA工艺,那么航空航天复合材料的制造将发生极大的变化。图片来源:NASA

膜状胶粘剂的发泡,也可以使空气迁移到表皮,这会影响胶粘带的形成,进而损害表皮和芯材的粘接质量。许多用于蜂窝夹芯的普通膜状胶粘剂,在OOA加工中所使用的高真空水平下都会发泡。ACG公司发现,发泡受到膜状胶粘剂载体的类型、蜂格尺寸和固化温度的影响。该公司通过对这些变量进行研究,开发了MTA241,它与MTM材料相容,并且在标准的OOA固化循环内不会发泡。“我们知道,VBO工艺需要一整套的OOA材料。”波音公司的Hahn说道。美国空军研究实验室(AFRL)的Russell也同意这种观点,他说:“膜状胶粘剂和膏状胶粘剂需要与OOA系统相容。当OOA向前发展时,整套材料都必须是相容的。”

OOA蜂窝夹层的另一个问题是避免单次固化时发生表面点蚀。“一个漂亮的OOA夹层表面需要有一层表面齐整的薄膜。”Hahn说道。在最近为2个1.2m×2.4m的测试面板进行的试验中,其中一半使用了表面薄膜,另一半没有使用,结果有薄膜的一半形成了一个更好的表面(没有表面孔隙)。ACG公司不太担忧表面点蚀的问题,因为其在热压罐固化夹层结构中经常使用表面薄膜作为铜网或其他防雷保护(LSP)材料的载体。ACG公司已开发了MTM246表面改善薄膜,用于它的OOA预浸料,而氰特公司推荐其灵活固化的SurfaceMaster SM 905产品,该产品已被用于许多OOA项目中。

更高的浸渍用于自动化

自动化已成为OOA发展的一个关键领域。非热压罐复合材料的纤维铺放是2009~2011年的一个研发项目,由国防部长办公室(OSD)、美国空军研究实验室(AFRL)、国防后勤局(DLA)和海军研究办公室(ONR)制造技术计划联合资助。该项目的主要目标是开发用于OOA材料的自动纤维铺放(AFP)工艺,包括关键工艺参数的确定,如铺放速率,并通过制造全尺寸的航空航天部件来验证该过程。参加者包括波音圣路易斯公司、GKN公司、HITCO碳复合材料公司、洛克希德马丁公司和Spirit空间系统公司。该项目所使用的自动化设备则来自于ElectroImpact公司、Ingersoll机床公司以及MAG工业自动化系统公司。

据Ridgard称,大多数用于手工铺层的OOA预浸料在一定程度上结合了干纤维的工艺路线,它允许在固化过程中抽取空气,但结果不能形成100%的浸渍。这就是使用编织紧密的E玻纤或石英织物的OOA预浸料得不到充分浸渍的原因。然而,在AFP中使用的材料通常要求具有更高的浸渍水平。氰特公司解释说,自动铺带(ATL)中使用的OOA预浸料被分割成152~305mm的宽度,它们不像一般用于AFP的3.2mm、6.4mm或12.7mm窄带子那样敏感。在这些带子中没有干纤维,因为带子铺放时,干纤维移向边缘并聚集,而带子在使用时其边缘会发生脱落。这可以解释为什么用于AFP的OOA预浸料可能和VBO系统虽具有相同的化学性质,但它经常使用最高的浸渍水平。

尽管如此,假定AFP应用的边缘压紧力以及在压力和热量下材料的铺放能力能够减轻空气夹带的问题,氰特公司仍然建议自动铺带采用和手工铺层OOA层压板相同的真空保持度。“这个问题和其他问题正被前面提到的OSD纤维铺放项目所研究探讨,”Russell称,“我们不知道铺带边缘的压力是否将阻断空气路径,这可能会导致孔隙度出现问题。”MTM-45和CYCOM 5320-1将被评估,用于AFP制备的战机机翼表皮部件中。该项目将比较各类自动化设备,并以相同方式跟踪每个样件的铺放时间,所用标准是由联合攻击战斗机(JSF)项目制定的标准。

GKN公司应用其在OOA材料自动化铺层方面超过10年的经验来生产10.5m长、全截面碳纤维复合材料的翼梁样件,该部件和为A400M军用运输机提供的前后翼梁相似,后者是2005~2009年空中客车公司领导的先进低成本飞机结构(ALCAS)项目的一部分。在生产过程中,首先一台西班牙MTorres公司提供的11轴龙门式高速铺带机使用HTS 268g/m2的碳织物MTM44-1预浸料进行铺层;然后这种“扁平带”被自动地转移到碳纤维模具中,模具再被放入一台双隔膜成型压力机中,20min后成型为C型截面半成品;该层压半成品再经过袋压和固化(采用真空压力,所需热量来自集成在模具中的电器元件,初始固化温度为130℃,后固化温度为180℃),一个27mm厚、孔隙率<2%的翼梁部件就得以制造完成。该样件目前正在空中客车英国公司进行测试。

采用加热的模具已经成为GKN公司固化OOA的传统方法。“电或液体加热的模具使你能够不使用热压罐和热炉,”Rich Oldfield说道,“它还允许更精确地控制固化过程,包括局部加热,以适应不同厚度的部件,并消除热点和冷点。”GKN公司认为即使整体加热的模具,其成本也只比标准模具略高一些,但它大大缩短循环时间以及摆脱传统约束的好处提供了一个整体上的经济收益。此外,这项技术也非常有利于更高速的制造。

批评者争辩说,自动化铺层依然依赖大量的资金成本,因此这只是“换汤不换药”。而GKN公司却进行了机器投资,它认为与OOA固化相结合的自动化铺层会带来非常显著的成本节省。自动铺层也不必像典型的手工铺层那样,因使用了预浸料支撑薄膜而需要对产品进行100%的检测。

BMI和超越

OOA双马来酰亚胺(BMI)系统的开发,是OOA工艺发展中一个“安静的革命”。直到Russell在盐湖城召开的秋季SAMPE会议上称:这应该成为每一家公司的一个目标,BMI 才为业界所关注。ACG公司在今年5月份通过演示宣布,它正在开发一种OOA BMI,并将在2011年年底之前完成筛选,2012年产生数据。氰特公司也表示,它将开发OOA BMI。

Maverick公司已生产聚酰亚胺树脂达17年之久,并向预浸料制造商销售这类树脂,如Renegade材料公司。事实上,Maverick公司和Renegade材料公司自2008年以来,就保持密切合作。最近,Akron聚合物系统公司和NASA Glenn公司作为合作伙伴也加入进去,共同开展OOA材料用于高温复合材料应用项目的研究。这项工作受益于最近从美国俄亥俄州获得的Third Frontier Grant基金。该团队自筹和俄亥俄州的配套资金将在两年内达$200万,在此期间,他们将开发使用温度达204~371℃的BMI和聚酰亚胺系统。

Maverick公司总裁兼产品开发总监Robert Gray博士称,聚酰亚胺的使用温度为204~371℃,成本在$220~551/kg之间,而BMI树脂可提供高达177℃的热/湿性能,成本仅为$154~220/kg。BMI树脂更容易加工,因为其不像聚酰亚胺在固化过程中会产生反应副产物,例如水和乙醇。Gray相信大多数加工厂受限于加工只针对高温应用的BMI材料。因此,Maverick公司计划在配制VBO固化预浸料时采用分子量更高的系统以代替粘度非常低的树脂,来减少加工聚酰亚胺的复杂性。

聚酰亚胺复合材料的军事用途包括:喷气发动机中的导向压缩机的定子叶片、发动机背后的排气瓣及外部旁路管道。聚酰亚胺结构也可以应对商业飞机发动机里面和周围的极端环境。Maverick公司和Renegade公司已经确定了聚酰亚胺的许多结构性应用,包括无人机(UAV)和隐形应用。通过提供加工更经济的OOA聚酰亚胺,Maverick公司的项目可以帮助飞机设计师通过减少绝缘和屏蔽的需要来减轻部件的重量。这对于对重量异常敏感的运载火箭和其他空间平台尤为重要。

目前,PMR-15(氰特公司提供的牌号为2237 CYCOM)是行业标准的聚酰亚胺,需要在1.38MPa进行热压罐固化。Gray解释说:“复合材料制造商很少有大型的高温热压罐。如果我们能脱离热压罐加工聚酰亚胺,就可以极大地增强高温复合材料部件供应商的能力,并扩展这些轻质材料的应用。”

然而,推动OOA BMI的因素是什么呢?行业顾问Jeff Hendrix认为,大多数要求耐热温度在135℃以上的BMI和聚酰亚胺部件都被用于发动机中,并且通常要求它们的尺寸不是很大。这些部件适合于目前的热压罐工艺,实际上大多数是模压成型的。“不是使用温度高促使人们选择BMI,而是其在较低温度下的卓越缺口冲击性能使它们对许多方案都有吸引力。”Hendrix解释道,“真正令人满意的OOA系统是其可以在82~121℃范围内匹配BMI的缺口冲击性能,这对环氧树脂基系统颇为理想。”

美国空军研究实验室(AFRL)的Russell表示同意,并指出:“5250-4 BMI(氰特公司生产)被大量地用于JSF项目中,该应用不需要较高的工作温度,选择5250-4 BMI仅仅是因为其热/湿性能提供了更高的比刚度和比强度,进而能够实现更轻的结构。”

Russell还看到了将来的项目对于更高耐温性能的需求,他说:“一些涉及联合未来战区运输机的概念,将催生一种类似于巨大的F-22的运输机,其发动机紧挨着机身,排放的废气穿过水平尾翼表面。这些主结构的温度可能会超过环氧树脂的耐热能力。因此,我们对OOA BMI感兴趣。”Russell称,NASA对BMI产生兴趣的原因是,在运载火箭的头锥使用BMI可以避免使用昂贵、笨重的绝缘材料。单单减轻重量就足以证明使用更贵的BMI是合理的,更不用说它还有利于原材料和劳动力的节省。“我们与Stratton复合材料公司有$60万的合作项目涉及非热压罐BMI的开发。”Russell指出。

波音公司的Hahn说:“有些人看不到OOA BMI所带来的许多好处。作为一家飞机制造商,我会问材料供应商,他们是否有一种OOA BMI可在相当低的固化温度下可以达到足够的初始强度。因为开发新的项目时,所要求的使用温度通常升高而不是下降。”

不再使用热压罐吗?

NASA的复合材料结构高级顾问Mark Shuart谈到,当截面直径为10m的部件被证明可以采用OOA成功加工时,航空航天复合材料的制造将会呈现很大的相同。但有些人会说没有那么简单。“对于要采用的技术来说,它必须具有经济意义。”Hahn说道。Hendrix表示同意。“如果你的生产计划已经有了一个热压罐和材料数据库,那么你不必刻意采用OOA,”他说道,“只有从原型到生产更经济,或者为大型共固化结构件减少模具的复杂性,才会有意义。”

氰特公司的Mark Ostermeier预测,OOA中会更加占据主导地位。但他警告说,航空航天业将仍然是保守的。“庞巴迪公司的Learjet机型在谋求一个全OOA复合材料机身方面已经迈开了一大步,”他说道,“但大多数厂家的大型商业结构件可能还在等等再看。”

Ostermeier看到军用航天航空领域走向OOA的速度比商用飞机更快,并且如果NASA可靠地生产出非热压罐的运载火箭,他预测这可以相当大地改变复合材料的制造方式。Hendrix对此保持怀疑,他说:“我相信OOA的前途是光明的,但人们应该小心,因为他们认为它十分便宜。”

Hahn认为,OOA用于实际生产和研发项目的功效比较是一个大问题,决策的推动力往往是一个项目的截止日期。“我们正在考虑的OOA材料的成本与使用的热压罐主结构材料相同,”她说道,“如果这些OOA材料允许我们在6周内完成模具,然后更快速地进行原型开发和生产,那么它们可以在针对某一应用的商业开发中获胜。”

性能要求:CAI与OHC

美国空军研究实验室(AFRL)非热压罐研究项目的负责人John Russell最近在犹他州盐湖城召开的秋季SAMPE会议上宣称:“使用没有微裂纹的高模量纤维,可使我们提高25%的缺口冲击性能。”尽管OOA预浸料供应商在减少纤维微裂纹方面做得不是很多,但ACG公司已经宣布其XMTM47材料将于明年商业化,该材料的设计基于120℃的使用温度及所要求的缺口性能的改善。缺口压缩强度通常采用开孔压缩(OHC)实验来测量。ACG的XMTM47材料的目标是104℃湿法OHC 达到43ksi。现有的一个更韧性的系统如MTM45-1的OHC约为35ksi。

然而,根据NCAMP(国家先进材料性能中心)副主任Yeow Ng所言,如果OOA预浸料被用于商用飞机,则其压缩后抗冲击性能(CAI,表明损伤容许度)将增加。在Stephen Trimble为《Flight Daily News》最新撰写的文章中,Ng指出,MTM45-1达不到商业飞机监管机构所要求的强度公差。 波音787结构的冲击后压缩(CAI)强度的测量值是40s(ksi),但MTM45-1的CAI 值在30ksi以下。

ACG公司的研究和技术副总裁Chris Ridgard回应道:“许多用在Hawker Beech、Embraer、Gulfstream以及庞巴迪飞机中的结构件都是用热压罐固化Hexcel 8552(CAI≈30 ksi)和氰特977-2(CAI≈37ksi)预浸料制成的。”他还指出,用于Learjet 85、正在进行资格认证的CYCOM 5320,其公布的CAI值为26.5ksi。他说:“在OOA成为一种趋势之前,这种辩论已经存在很久了,它起始于20世纪70年代的热压罐材料和建立在特定应用需求基础上的不同设计理念。”曾是英国航空航天公司结构工程师的Ridgard解释道:“军事上的应用是被缺口应变推动的。军事应用要求结构上的任何地方都可有一个孔存在,并提供一定程度的余量用于战斗损伤和螺栓的维修。因此,军用飞机都倾向于使用具有较高OHC值而韧性较低的树脂系统。” 他继续说道,“对于具有相对较少扣件的大型结构件的大型商用飞机来说,一些飞机制造商偏好使用具有极高CAI值和高破坏应变的高增韧树脂系统。”

ACG公司称将开发一种CAI高于40s的OOA系统,这是一种高度增韧的系统,用于商用飞机领域。氰特公司称,这也将是其下一个工作的重点。当被问及是OHC还是CAI推动Aurora飞行科学公司的无人机设计时,该公司的结构工程师Ed Wen回应道:“两者都有推动作用。”这与波音公司Gail Hahn的观点一致:“我们知道采用不同材料系统的重要性,因此我们将采用一系列的OOA预浸料来满足不同的设计要求。”

真空粘接蜂窝夹层

在《先进复合材料的保养和维修》一书(由汽车工程师协会所属的Warrendale公司在1997年出版)中,英国航空公司拥有复合材料制造和修复24年经验的Keith Armstrong博士讲述了有关“在蜂窝中,单独用0.1MPa的真空获得足够的膜状胶粘剂的粘合压力”的问题,他写道:当真空泵开始从真空袋中抽取空气时,一些空气从蜂格中去除,尤其是靠近板材的边缘。然而,当真空压力增加时,膜状胶粘剂在蜂格的两端形成一个密封,并且空气不再被抽取。

在英国航空公司的试验中,一块边长为0.3m的正方形测试板因真空条件下加热造成的内部压力而不能在中心区域粘接。Armstrong称,在120℃固化过程中,甚至更高的180℃固化中,蜂格内的压力将增加1.5倍,因此他建议相应地减小蜂窝夹层内的压力。对于120℃的固化,如果一个0.1MPa的真空施加于蜂窝夹层,则夹层内的压力在加热之前需要减小到4MPa。Armstrong解释道:“这种非穿孔蜂窝板的制造技术,是在胶粘剂和蜂窝之间夹层的一个面上使用了一种合适的织物。英国航空公司选用了一种无纺聚酯单丝织物,有时也被称为定位布,它通常用作膜状胶粘剂的载体,具有较低的吸水性能。

他强调说,无论选择什么织物,其厚度不应超过0.076mm(英国航空公司选用的两层织物的厚度为0.038mm),膜状胶粘剂应包括1层1.36kg/m3层或2层0.096kg/m3层,以确保能有足够的胶粘剂量来吸附织物,并且在表皮和蜂格末端之间形成充分的胶粘带。

原文资料:

Out-of-autoclave prepregs: Hype or revolution?

Producing aerospace composites without an autoclave, using vacuum-bag-only (VBO) atmospheric pressure, is nothing new. Vacuum-bagged, oven-cured material systems for secondary structures (flaps, fairings and the like) are well established. What is new is the ability for such materials to deliver the less than 1 percent void content and autoclave-quality mechanical properties required for aerospace primary structures, such as wings, fuselages and empennage components with integrated stiffeners.

Interest in OOA processing also has spurred the use of resin transfer molding (RTM), vacuum-assisted RTM (VARTM) and other liquid molding processes as well as the latest generation of compression molded thermoplastics (see “Aerospace-grade compression molding,” under "Editor's Picks," at top right). Although these processes are gaining acceptance among those who fabricate highly loaded structures, VBO prepregs, which encompass traditional hand layup as well as automated material placement methods, are of particular interest due to a combination of unique advantages.

The U.S. Air Force has identified OOA prepregs as vital to achieving the fast and affordable manufacturing that the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) will require for future military platforms, and the Air Force sees additional cost savings when one OOA prepreg system can be used for prototyping, production and spares. Suppliers to commercial aircraft OEMs see OOA materials as a way to achieve manufacturing flexibility, freeing them from size constraints and enabling modular/cellular workflows.

Yet many issues remain. OOA cycle times might actually be longer, due to the time-dependent process of edge-breathing required for low void content. Other issues include compatibility of adhesives, surface quality of sandwich structures, and using automation in lay-up. Also, because these materials are new, a complete database of B-basis design allowables will have to be established, requiring time and money.

“Aside from the hype, is OOA a good tool?” asks Gail Hahn, Non-autoclave (Prepreg) Manufacturing Technology program manager at Boeing Research & Technology (St. Louis, Mo.), “Yes, but is it a game changer for all applications in the industry? Not necessarily.”

Why OOA prepreg?

OOA prepregs ensure even resin distribution, avoiding the dry spots and resin-rich pockets common with infusion processes. Also, OOA prepregs can be cured at lower pressures and temperatures (vacuum pressure vs. a typical autoclave pressure of 85 psi and cure at 200°F/93°C or 250°F/121°C vs. a traditional 350°F/ 177°C autoclave cure). Therefore, tooling for large composite structures with integrated stiffeners that can be cocured in a single cycle, which is typically very complex and expensive, now might be fabricated much more simply and cost-effectively. Further, mismatches between tool and part coefficients of thermal expansion (CTEs) are smaller at lower temperatures and, therefore, more easily managed, positioning OOA prepregs as a potential solution for part cracking caused by cure-temperature differentials.

One of the most widely cited OOA benefits is the potential to reduce high capital and operating costs. John Russell, Defense-Wide Manufacturing Science and Technology program manager for the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio), relates that NASA explored the costs of building a 40-ft by 80-ft (12m by 24m) autoclave to cure 10m/33-ft diameter launch vehicle barrels and found that it would cost roughly $40 million to build and another $60 million to install, plus the cost of nitrogen and power to operate it. DoD advisories indicate that future military aircraft programs will be produced in small volumes with very small budgets. Future NASA programs will be cost-constrained to an even greater degree. Russell points out that for NASA and for coming DoD programs, such as the Long Range Strike and Joint Future Theatre Lift (the latter a C-130 successor with planned 180-ft/55m wingspan and 140-ft/43m fuselage), “the challenge is how to deal with low production volumes —100 aircraft — while reducing capital requirements as much as possible.” The Air Force foresees a huge savings from the elimination of autoclave capital and operating costs.

Tier 1 suppliers to commercial aircraft OEMs agree, seeing OOA prepregs as a way to attain faster, more agile manufacturing. “We will pursue nonautoclave manufacturing for as many parts as is feasible in the future,” comments GKN Aerospace (Redditch, Worcestershire, U.K.) director of technology, Rich Oldfield. “We see it as a way to bring efficiency to the factory, including an entirely different workflow due to cellular manufacturing vs. large parts queued up for an autoclave.” GKN also sees this flexible manufacturing, which is less reliant on traditional manufacturing monuments, as critical to the task of achieving the forecast 60 to 70 percent composites content on the next generation 737 and A320 single-aisle jetliner programs.

A revolution 20 years in the making

According to Russell, AFRL and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) began to look at tooling prepregs and how they might be used to make prototypes in the Affordable Composites program during the mid-1990s. The first generation of OOA VBO materials, including Advanced Composites Group’s (ACG, Tulsa, Okla. and Heanor, Derbyshire, U.K.) LTM series, enabled cheaper, low-temperature vacuum-cure prototypes of large, unitized parts. Notable examples: Scaled Composites’ (Mojave, Calif.) SpaceShipOne, WhiteKnightOne and Global Flyer, Boeing’s X45A unmanned combat aerial vehicle (UCAV), DARPA/Lockheed Martin’s Darkstar, and the McDonnell Douglas Bird of Prey.

These early prepregs were cheaper because they cure at lower temperatures under vacuum pressure, but they had neither the mechanical properties nor the sufficiently short cycle times necessary for production parts.

By 2005-2006, two OOA prepreg systems — ACG’s MTM45 and Cytec Engineered Materials’ (Tempe, Ariz.) CYCOM 5215 — were approaching the properties of autoclave-cured prepregs. Both prepregs feature flexible cure cycles, requiring longer cure times at 150°F to 175°F (66°C to 79°C) but providing shorter two-hour cures at 250°F/121°C. Additionally, they achieve a wet Tg of more than 300°F/150°C after a 350°F/177°C freestanding postcure.

These systems achieved DARPA’s required <1 percent void content, but fell short elsewhere. The 10- to 12-day tack life and maximum 21-day open mold life were deemed insufficient by both AFRL and NASA because layup and bagging of large, complex structures require, at minimum, three to four weeks. Recently, however, ACG and Cytec have developed XMTM-47 and CYCOM 5320-1, respectively, targeted to a longer tack life of 21 days and minimum 30-day open mold life.

In 2007, the Disruptive Manufacturing Technologies Initiative began, with Non-Autoclave (Prepreg) Manufacturing Technology as one of five concentration areas. Cofunded by DARPA and Boeing, and executed with AFRL, the Non-Autoclave initiative’s established goal was to develop OOA systems that could provide the same performance as currently qualified autoclave-cure epoxy materials. ACG responded with MTM45-1, MTM-44 and MTM-46 and Cytec responded with CYCOM X5320. Boeing evaluated three experimental resin formulations, and selected X5320, which was later commercialized by Cytec as CYCOM 5320.

A range of demonstrator parts were built and subjected to limited nondestructive and dissection evaluations. HITCO Carbon Composites (Gardena, Calif.) built a 3.65m by 4.57m (12ft by 15 ft) hat-stiffened skin primary structure demonstrator. Aurora Flight Sciences (Columbus, Miss.) built a 38-ft/11.6m unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) wing spar. (In a separate development, Aurora built a three-part, OOA-cured wing structure with a 150-ft/45.7m span for the Phantom Eye UAV demonstrator, which won top honors in Aviation Week’s Supplier Innovation awards competition, as a potential game-changer in the industry.). Boeing (Irvine, Calif.) built the boom and empennage for a 60 percent-scale demonstrator of the long-endurance Phantom Eye UAV, which is scheduled to begin flight trials in early 2011. Boeing has also submitted draft material specifications for carbon prepreg and a draft process specification, which are available to the public.

As part of the program’s Phase II, Boeing’s St. Louis operation manufactured 68-ft/21m parts, including a spar and three different wing skin configurations:

A plank-stiffened skin, using Grafil (Sacramento, Calif.) HR 40 12K high-modulus carbon fiber;

A hat-stiffened skin. using Cytec T40/800B intermediate modulus carbon unitape as well as high-strength fabric made from Cytec Thornel T-650/35 3K carbon fiber;

A sandwich construction skin, using nonmetallic honeycomb core.

All were made with the same tooling, enabling Boeing to compare the finished panels in terms of quality, degree of production difficulty, inspectability and technology maturity level.

Perhaps the most successful demonstration of large OOA-cured structure to date is the Advanced Composite Cargo Aircraft (ACCA). When tasked by the Secretary of the Air Force to develop a new military transport aircraft with only $50 million and (indicative of DoD’s future intentions) 18 months to completion, Lockheed Martin (Ft. Worth, Texas) responded to an AFRL Broad Agency Announcement (BAA) competitive solicitation with a Dornier 328, cut off behind the cockpit to avoid the expense of developing new flight controls, and added an all-composite, 60-ft/18m long fuselage, built in eight pieces using ACG’s VBO-cured MTM-45 throughout the structure. Although the program ran seven months past its deadline, AFRL’s Russell, the program’s manufacturing engineer, says ACCA stayed on-budget and was a success (see "Advanced Composite Cargo Aircraft ....” under "Editor's Picks").

Ready but awaiting qualification

OOA prepregs have now reached physical property parity with autoclave-cure systems for primary aircraft structure, and several are already in qualification processes. The National Center for Advanced Materials Performance (NCAMP, Wichita, Kan.) has completed allowables testing for CYCOM 5215 and nine MTM45-1 product forms, including uni and woven quartz fiber, plain-weave G30-500 carbon fiber, high tensile strength (HTS) 12K carbon uni, E-glass, and 6781-style S-2 glass prepreg, with fiber supplied by AGY (Aiken, S.C.) and woven by JPS Glass Fabrics (Anderson, S.C.). NCAMP testing of the same nine systems for MTM46 and also for CYCOM 5320-1 will soon be completed. ACG has announced that it will be releasing allowables for its XMTM47 system (“X” soon to be removed) in 2011 via its Lightweight Composite Structures (LCS) program with NAVAIR.

However, there is debate in the industry with regard to qualification and the availability of a complete allowables database. “We are at quite a high readiness level with our OOA technology and could deploy it into products relatively quickly,” says GKN’s Rich Oldfield, “except for the lack of availability of qualified materials, because there is no B-basis allowables database currently for any OOA prepreg system.” This FAA-approved statistical design data from composite lamina and laminate batch testing is a prerequisite to qualification for use in military or commercial aircraft primary structure. ACG’s VP of research and technology, Chris Ridgard, explains, “NCAMP does not run every test that defense airframers list as necessary.” It also does not run as many samples as defense programs require — approximately 1,400 to 1,500 vs. the 3,000 for defense qualification. “NCAMP tests materials and stores the values in a database, but only a specific defense platform can qualify a material for use on that vehicle” explains AFRL’s Russell. “It typically costs $3 million to $5 million to develop a complete B-basis allowables database, and none of the suppliers has stepped up to the plate just yet.” Russell notes that NCAMP testing offers data that is not held as proprietary by any one company or defense platform, such as that developed in the ongoing qualifications at Bombardier and Airbus.

Cytec product manager Mark Ostermeier says CYCOM 5320 and 5320-1 are being qualified in separate, proprietary programs. Cytec has announced it will supply carbon fiber composite materials for both primary and secondary structures on Bombardier’s (Montreal, Quebec, Canada) Learjet 85, and Bombardier reported that the pressurized fuselage will feature “a low-pressure, oven-cured, out-of-autoclave carbon fiber supplied by Cytec.”

ACG’s OOA materials are in qualification at Airbus. David Inston, project leader, out-of-autoclave technologies at Airbus’ Bristol, U.K. location, explains, “MTM44-1 is qualified with an Airbus specification for a particular 2x2 twill fabric. However, it is not fully qualified yet for a specific application.” Although this is a woven fabric specification and, therefore, will be used for secondary rather than primary structure, qualification is nearly complete and marks the first use of MTM44-1 for an actual aircraft part. Airbus has an agreement with GE Aviation (Hamble, U.K.) for the production of secondary wing structures for the A350, including wing access panels and trailing edge details. Inston notes that Airbus does have a specification published for an MTM44-1 unidirectional product, but no further qualification testing has been launched yet for a particular application, although a primary structure demonstrator has been built. “Airbus is in the process now of defining its road map to further develop OOA materials, including potential use in primary structures,” he adds.

Long time for low porosity

Manufacturers, however, warn against unreasonable expectations for OOA prepregs in production. Their reputation for “fast” prototyping, for example, might not translate to “fast” production, where void content goals can’t be compromised. ACG’s Ridgard explains that in OOA processing, removal of volatiles, which include not only air entrapped during layup but also the moisture (1 to 2 percent) that epoxies absorb when they are exposed to ambient air, involves an “edge-breathing” strategy. The laminate edges must be in contact with the breather and materials must be arranged in a way that maintains air escape paths. The vacuum bag materials and sequence are the same as with autoclave processing, but vacuum quality is vital, and because entrapped air extraction is a time-dependent process, OOA cure cycles are typically longer. Cytec recommends a vacuum hold before initiating cure for parts made using its OOA prepregs. This is in addition to any debulks required during layup and is performed without removing the bag prior to cure. Hold length depends on the part size and complexity, ranging from as low as four hours for a 2-ft by 2-ft (0.6m by 0.6m) part to 16 hours for a 20-ft by 40-ft (6m by 12m) structure with cocured hat stiffeners.

But John Cornforth, GKN Aerospace’s head of technology, cautions, “You have to be careful when you talk about OOA taking more time in vacuum, because some autoclave materials also require long vacuum times.” He notes that it is very hard to compare alternative systems because the specific process details of vacuum presssure, cure temperatures and cycle times become very dependent upon the specifics of each part.

ACG’s Ridgard asserts that the overall time penalty is really not any greater than with autoclave production: “If you cure MTM45-1 at 350°F [176°C], for example, you have to dwell at 250°F [121°C] for two hours because ramping too high too quickly drops the resin viscosity to where it will block off air paths. You are only adding two hours, plus you have the flexibility of a longer cure at 250°F [121°C] or 200°F [93°C], where the extra vacuum time is built-in, and then do a freestanding postcure to get the same properties.”

GKN, however, may have found a way around the extra cycle time. The company has developed microwave curing, which reduces typical cure cycles for both autoclave and OOA materials by up to 80 percent, to only 90 minutes. Microwaves reportedly heat only the composite structure, while the tooling and oven chamber remain cool, which drastically cuts heating and cooling time, as well as energy consumption. GKN sees an additional benefit in the ability to selectively cure parts of the structure, which could make integrating partially cured structures and then cocuring the final assembly possible in the future. GKN has begun technology readiness development, using ACG’s MTM materials, and is currently comparing traditional autoclave materials and processes with microwave curing, to define optimum parameters.

Sandwich surface and OOA adhesives

In its significant work with OOA-cured honeycomb-cored sandwich structures, ACG has identified some technical challenges. Chris Ridgard explains, “the bagging and layup techniques are basically the same as in autoclave curing, but venting of the core becomes important.” The high pressures used in autoclave curing, which do not permit air inside a honeycomb core to flow into skin laminates, are not present in OOA curing. Therefore, air must be removed from the core cells before the resin softens, because the lower OOA pressure might otherwise allow air to flow into the skin, resulting in high void content. Research performed at McGill University (Montreal, Quebec, Canada) and presented in a 2010 SAMPE paper shows that if pressure inside the honeycomb is reduced to 500 mbar (7.25 psi) or less prior to heating, the air does not escape into the facesheets. Instead, it remains in the core during the cure cycle. Ridgard says a lightweight glass fiber mesh (such as a 54 g/m2 or 1.6 oz/yd2 leno weave) is used as a breather to prevent skin disbonding due to pressure within the core. This technique was established at British Airways for composite repair more than 25 years ago (see “Old is new ...." sidebar, at the end of this article, or click on it under "Editor's Picks"). However, some believe it is not an optimal solution because the breather is laminated into the sandwich, increasing parasitic weight.

Air also can migrate into the faceskins due to foaming of the film adhesive, which compromises the adhesive fillet formation and resulting faceskin-to-core bond quality. Many common film adhesives for honeycomb sandwich will foam under the high vacuum levels used in OOA processing. ACG found that foaming was affected by film adhesive carrier type, honeycomb cell size and cure temperature. The company worked through these variables to develop MTA241, which is compatible with its MTM materials and will not foam during standard OOA cure cycles. “We see that a whole suite of OOA materials is needed for VBO processing,” says Boeing’s Hahn. AFRL’s Russell agrees, “Both film and paste adhesives compatible with OOA systems are needed. As OOA moves forward, the complete materials suite must all be compatible.”

Another issue for OOA honeycomb sandwich is to avoid surface pitting with single shot cures. “Surfacing film is required for a beautiful OOA sandwich surface,” says Hahn. On two recent 4-ft by 8-ft (1.2m by 2.4m) test panels where half used a surface film and half did not, the half with the film produced a better surface without surface porosity. ACG is not too concerned, because autoclave-cured sandwich structures often use a surfacing film as a carrier for copper mesh or other lightning strike protection (LSP) materials. ACG has developed MTM246 Surface Improvement Film for use with its OOA prepregs, while Cytec recommends its flexible-cure SurfaceMaster SM 905 product, which has been used in many OOA projects.

Higher impregnation for automation